- Home

- Donald Hamilton

The Wrecking Crew Page 11

The Wrecking Crew Read online

Page 11

She was very intent, very serious, and I knew she was trying to tell me something important. “I’ll remember it,” I said. “And I’ll make no more derogatory remarks about Mr. Taylor. Okay?”

Lou smiled quickly. “I didn’t mean to sound as if… Well, maybe I did.” She brought out her long cigarette holder, loaded it, and applied a match before I could act like a gentleman. “Now,” she said, “you tell me about your wife, and we’ll have all that out of the way.”

I glanced at her. “I never told you I had a wife.”

“I know you didn’t, darling. It was very deceitful of you, but I already had the information. You have a wife and three children, two boys and a girl. Your wife is getting a divorce in Reno on the grounds of mental cruelty, after fifteen years of marriage. It certainly took her a long time to discover that you’re a brute.”

I said, “Beth is a nice, sweet, bright, somewhat inhibited New England girl. She thinks wars are fought by brave men in handsome uniforms, engaging each other in open combat according to the rules of civilized warfare and good sportsmanship. Even so, she thinks it’s dreadful. She was very glad that I’d spent the war behind a desk in a public information office and hadn’t killed anybody. That was the story I told around, under orders. When she learned it wasn’t the truth, she couldn’t make the adjustment. I wasn’t the same person; I wasn’t the man she’d married. I wasn’t even anybody she’d want to marry. There was nothing left but to call it a day.” I glanced out the window, and saw with relief that our transportation was outside. The conversation had been getting slightly personal. “Finish up your coffee quick,” I said. “Our escort is waiting.”

I used more color on the job today because of the bad light. Black-and-white depends largely on highlights and shadows, not only for effects, but even for sharp details. On a cloudy day, it’s hard to get useful black-and-white shots of intricate industrial subjects, particularly with a small camera that, necessarily, doesn’t yield the ultimate in sharpness. Color, on the other hand, is almost easier to handle on a cloudy day than otherwise, since it doesn’t tolerate or require strong contrasts of light and shade. With color, the colors themselves provide the necessary contrasts. If you don’t insist on gaudiness, you can get some wonderful color stuff under lousy weather conditions.

We had a little rain, but not enough to drive us to cover; and we finished up around two o’clock without having stopped to eat. I spent the ride back to town worrying about the tipping problem, and settled by shaking hands with Lindström, our young guide, and thanking him for all his trouble. Then I slipped the middle-aged driver five crowns, the equivalent of a buck, which didn’t seem to excite him tremendously, but he didn’t throw it away, either.

“Let’s get something to eat uptown,” I said to Lou after we’d hauled my stuff up the stairs. “I’m getting kind of tired of the hotel food.”

“All right,” she said, “just give me a couple of minutes to change my socks and scrape the mud off my shoes.”

I went into my room to wash up—also to perform my little switch routine with the day’s films. Then I went out to the car. I never like to drive a car that’s been standing around, while I’m on a job, without first giving it a quick inspection, and this one had spent the night far from home.

The Volvo was standing in the hotel parking space with nothing but somebody’s Triumph motorcycle for company. I walked around the little sedan once and looked inside; it was empty except for a rug or blanket provided by the management, which had slid off the rear seat onto the floor. I decided to take a chance on the doors; generally, if they have the vehicle booby-trapped, they prefer to let you get inside before they blow you up, since the explosion has a better crack at you in a confined space.

Nothing happened when I opened the door. I got the hood open. The little four-cylinder mill looked all right to me. There didn’t seem to be any unnecessary wiring around the starter or its switch. I crouched to look underneath for signs that the brakes had been tampered with. There weren’t any, but something was dripping out of the differential housing.

I went around to the rear and held my hand under the drip and brought it out again. The stuff wasn’t any legitimate lubricant I’d ever met. It was thin and bright red like blood. Still crouching there, frowning, I saw that the source of it wasn’t the differential housing at all. The stuff came from farther forward. It was dripping through the floor boards of the car onto the drive-shaft and running back…

18

He was lying on the floor of the car, in the narrow space between front and rear seats, with his arms locked tightly across his stomach. I’ll admit I didn’t recognize him instantly. Curled up like that, he wasn’t showing much of his face, and it had been a long time since I’d known him well. He was dressed in rougher clothes than those he’d worn to visit my Stockholm hotel room, the night Sara Lundgren had been killed. It it was Vance, all right. I’d have thought him dead when I removed the blanket and saw him there, except that blood doesn’t usually run with any enthusiasm out of a dead body—once the heart stops pumping, there’s nothing to make it run except gravity.

I tried to reach a wrist to check the pulse, but he wouldn’t let himself go. I guess he had the usual gut-shot man’s conviction that those arms were all that was holding him together. Maybe he was right. Whoever had done the job had certainly got him there more than once.

“Vance,” I said. “Vance, this is Eric.”

I thought he didn’t hear me; then his eyelids fluttered. “Excuse... the hemorrhage,” he whispered. “Very embarrassing…”

“Yeah,” I said. “Let’s get you to a hospital. You can crack wise there.”

He shook his head minutely. “No time... drive me where… talk…”

I said, “The hell with talk. Just hang on while I find out where to take you in this town.”

“Eric,” he said in a stronger voice, “I want to report. I’ve been waiting several hours, hoping you’d come before… before…”

“All right,” I said. “Report, damn you, but make it fast.”

“The fiancé,” he whispered. “Named Carlsson. Much business on Continent. Raoul Carlsson. Little man—”

I said quickly, to save his strength: “Pass the description. I’ve met the gentleman. What did you find out about Wellington?”

If he had to tell it, the stubborn dope, I could at least hurry him through it. But he didn’t seem to hear me. He was off on another tack.

“Under no circumstances take action,” he breathed. “This is an order. This is an order. The soft, peaceful sheep in Washington! How can a man defend himself, if he is forbidden to kill? He was as slow as molasses in January. Fine old American expression, eh? Did you know I’ve never been back to the States since the war? Always some new job, some new place. Slow as... I shot him in the shoulder. All I could do, with those orders. Bah! He laughed and gave me this. Under no circumstances… Why not simply order us to commit suicide?”

“Who was it?” I asked. “Who got you, Vance?”

He shook his head. “Nobody. Just a nobody with a gun. Waste no effort on him. Just put another one into Caselius for me, when the time comes.” He frowned painfully. “Forgetting something. Oh, Wellington. You wanted to know about Wellington…”

“Never mind Wellington,” I said. “We’ve got to get you to a doctor now.”

“No,” he breathed. “No. Important. Must tell you about Wellington. Watch out for... Wellington is... He drew a long breath, and suddenly his eyes opened wide and he smiled a brilliant, bloody smile. “It is too bad, Eric. Now we will never know.”

“Know what, Vance?”

“Know if you could… take me…”

Then he was dead, with his wide-open eyes staring past me, seeing nothing, probably, although I can’t guarantee that, never having been there. Scratch Vance, a brave man who’d made his last report, not quite complete. It occurred to me I didn’t even know his real name. I got up and looked at my hands. They were red. W

ell, people don’t usually bleed any other color.

I heard footsteps in the gravel behind me, and turned to see Lou come running from the hotel.

“What is it, Matt?” she called. “You look so... What’s the matter?”

I walked slowly to meet her. She stopped before me, panting from the run. I said, “There’s a dead man in the car. We’ll have to notify the police.”

“A dead man?” she cried. “Who? Matt, your hands—” She tried to pass me, to look, but I put myself in front of her. I said, “I’m protecting you from a horrible sight, Lou. Turn and walk into the hotel ahead of me.”

“Matt—”

“Give me an argument, doll, and I’ll kick your teeth in. Turn and walk. He was a good man. He doesn’t want trash like you near him.” She got pale and started to speak and changed her mind. She turned slowly and walked toward the hotel. Walking behind her, I said, “You’ll forget I said anything to indicate I knew him.”

“Yes.”

“He’s a perfect stranger to both of us. We have no idea how he came to be in the car. We haven’t used the car since yesterday evening. It was left at Direktör Ridderswärd’s overnight. Don’t forget to bear down heavy on the title. It was driven here this morning by Fröken Elin von Hoffman—”

“You want me to say that?”

“Why not?”

“I thought you liked the girl.”

“Like? What’s like got to do with anything? I like you. Not very much right now, but I’ll get over it. But I’ll slit your throat at the first opportunity if you say one thing out of line; and if you think that’s a figure of speech, honey, just remember what I carry in my pocket and what my business is, and think again.”

She said, “Take it easy, Matt.”

I said, “Use the names. Ridderswärd. Von Hoffman. Honest, upright Swedish citizens. Maybe. Anyway, it’ll confuse the issue. And just keep clearly in mind that right now I’d just love to put my gory hands about your pretty neck and strangle hell out of you.”

She said, “I didn’t kill him, darling.”

“No,” I said grimly. “You have an alibi, if it happened last night, don’t you, sweet?”

She looked around, shocked, and said quickly, “You don’t believe—”

“Why not?” I said. “You went out into the night to get your instructions. You came back and followed them, no doubt, to the letter. It’s very convenient, isn’t it, that we’ve hardly been out of each others’ sight since midnight.”

She said, “Darling, I swear I had no idea—”

“Yes,” I said, “and you do swear real pretty, doll. And he probably wasn’t shot as long ago as last night, but they’d have you take the precaution of getting an alibi, anyway, not knowing exactly when their killer would make his touch. Or maybe you call it a hit, like the syndicate boys back home. But in our outfit we call it a touch. I hope to make one soon, myself.”

I drew a long breath. “Well, looking at it objectively, we’re in pretty good shape. You know I didn’t do it, and I know you didn’t do it—not personally, at least. And the company people have had us both in sight all day, thank God. But I think you know who did it. At least you know who’s responsible. Don’t you?” She didn’t answer. “Well, there you are,” I said. “A man’s been shot to death, but I don’t hear you volunteering the description, name, and present address of the murderer...”

The Kiruna police were polite and efficient. They were represented by a nameless officer in uniform and a plainclothes gentleman named Grankvist, whose exact status nobody bothered to explain. He was one of those lean, wiry, bleached-out Swedes. Even his eyebrows and lashes were pale, over pale blue eyes. There was a hint of something military in the way he stood and walked, but then, they’ve got conscription in that country, and every adult male has been exposed to a certain amount of drill and discipline.

We were questioned thoroughly and asked to present ourselves at poliskontoret in the morning, which we did. Here our statements were taken, signed, and witnessed, and we were told that we were free to go. Herr Grankvist himself drove us back to the hotel.

“I am sorry that you have been caused inconvenience by this unfortunate affair,” he said as he let us out. “I regret that we must keep the car in which the body was found a little longer. Its condition would hardly contribute to pleasant motoring, in any case. But if another car is required, arrangements could be made—”

I said, “No, just return it to the man from whom I rented it, if you don’t mind. Tell him that I’ll settle with him when I return to Kiruna next week. We’ve decided to take the train—that is, if it’s all right for us to leave town.”

He glanced at me in surprise. “But of course. Everything is all cleared up, as far as you’re concerned, Herr Helm. It was obviously just an unfortunate chance that caused the poor dying man to seek refuge in your automobile.”

He was a little too smooth, a little too polite, a little too reassuring; and when a foreigner speaks to you in English you can never be quite sure which of his inflections are deliberate and which are a matter of accent and accident. We watched him drive away.

Lou said thoughtfully, “Well, there’s a little man who isn’t exactly what he seems.”

“Who is?” I asked. “Come on. If we pack in a hurry, maybe we can catch the ten o’clock train out of here before he changes his mind.”

I turned toward the hotel doorway, but she didn’t move at once.

“Matt,” she said.

“Yes?”

“You were kind of rough yesterday. I didn’t mind at the time, because you’d obviously had a shock, but now you might say you’re sorry.”

I looked at her and remembered certain things about her—the kind of things you remember about a woman to whom you’ve made love. “I might,” I said. “But I’m not going to.”

She made a little face. “Like that, eh?”

“Like that,” I said. “Do you want to come along and help me shoot these pix of yours, or would you prefer to stay in Kiruna and sulk?”

There was color in her face, and her eyes were hot and angry, but the advantage was all mine and she knew it. She had to come with me. She had to supervise the taking of the pictures. If I’d had any doubts on that score, the way she swallowed her temper and managed to smile would have settled them for good.

“Just forget I brought it up,” she said lightly. “You’re not losing me that easily, Mr. Helm. I’ll be on the platform in ten minutes.”

19

I really had to hand it to the girl. Her motives might be questionable, her morals might leave something to be desired—not that I was in a position to criticize on that score—and her eye for pictures, while accurate, wasn’t characterized by much in the way of freshness and originality, but her talent for organization was awe-inspiring.

Usually, on a job like that, you spend half your time waiting for somebody to find a key to unlock a gate, or for somebody’s secretary to get back from a two-hour cup of joe so she can tell you the big boy’s left for the golf course and you’d better come back in the morning. There was no such monkey business here. Everywhere we came, they were expecting us; and I’d be led straight to the battlefield, aimed in the right direction, and told to commence firing.

In Luleå I thought she was going to spoil her perfect record. One morning, a polite but firm young lieutenant in the off-green uniform of the Swedish Army had come up to inform us that we were operating inside the military protection district of Boden’s fortress— that same mysterious fortification that had caused our airliner to make a detour the week before. In this district aliens weren’t even supposed to wander from certain designated public roads and areas, let alone set up enough photographic equipment to film a Hollywood super-colossal and proceed to make a careful documentary record of freight yards and docks.

Lou smiled prettily and displayed some official-looking papers, and the boy wavered and asked our pardon. But he had his instructions, and while everything was undo

ubtedly in perfect order, he would appreciate our accompanying him while he checked with his superiors.

We were working to a pretty tight schedule at the time, cleaning up this eastern end of the job so we could head back to Koruna, our headquarters, and work our way from there across the mountains to Narvik, in Norway. Any delay that particular morning would have scrambled our connections badly. Lou smiled at the boy again, and suggested he use a nearby telephone first, and call Överste Borg…

“How the hell did you manage that?” I asked, after the kid lieutenant had departed, with apologies. “I was all resigned to bars at the windows. Who’s Överste Borg?”

“Colonel Borg?” she said. “Oh, he’s an old friend of Hal’s. His wife’s a darling. They had me to dinner when I was here a few weeks ago. Come on, let’s finish up; we’ve got a plane to catch.”

It seemed as if the entire north of Sweden and substantial portions of Norway were populated by old friends of Hal’s, usually in fairly high official positions, all with darling wives. It made life very simple for a hard-working photographer. I asked no questions. I just went where I was led and did as I was told. It was a week to the day after Vance’s death that we wrapped up the job and took the afternoon train out of Narvik, which brought us into Kiruna Central Station on time at nineteen forty-five—a quarter of eight, to you. All official times in Sweden are given on the twenty-four-hour system, as in the armed forces back home. This saves a lot of A.M.’s and P.M.’s in the railroad time tables.

In my hotel room—the same one I’d kept right along—I changed to more respectable clothes. Our old friends the Ridderswärds were having us to dinner again. Waiting for Lou to let me know she was ready to go, I organized my films and equipment for, presumably, the last time on this particular jaunt. Then she knocked on the door and came in carrying her coat, purse, and gloves in one hand, and holding up her dress with the other.

The Two-Shoot Gun

The Two-Shoot Gun Mad River

Mad River Texas Fever

Texas Fever Ambush at Blanco Canyon

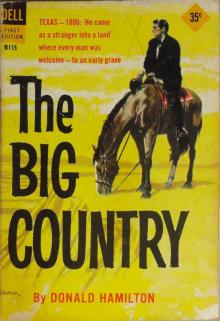

Ambush at Blanco Canyon The Big Country

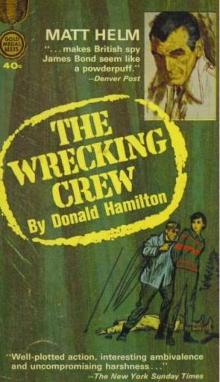

The Big Country The Wrecking Crew

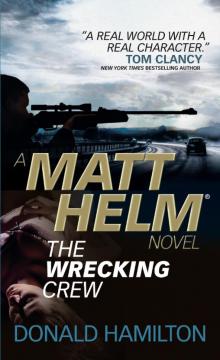

The Wrecking Crew The Devastators mh-9

The Devastators mh-9 The Wrecking Crew mh-2

The Wrecking Crew mh-2 The Shadowers mh-7

The Shadowers mh-7 The Ambushers mh-6

The Ambushers mh-6 The Betrayers

The Betrayers The Terrorizers

The Terrorizers The Poisoners

The Poisoners The Devastators

The Devastators The Silencers mh-5

The Silencers mh-5 The Interlopers mh-12

The Interlopers mh-12 The Shadowers

The Shadowers The Annihilators

The Annihilators The Vanishers

The Vanishers Night Walker

Night Walker The Revengers

The Revengers The Frighteners

The Frighteners The Infiltrators

The Infiltrators The Intriguers mh-14

The Intriguers mh-14 The Steel Mirror

The Steel Mirror The Menacers

The Menacers Assassins Have Starry Eyes

Assassins Have Starry Eyes Death of a Citizen

Death of a Citizen Matt Helm--The Interlopers

Matt Helm--The Interlopers The Removers mh-3

The Removers mh-3 The Demolishers

The Demolishers Murder Twice Told

Murder Twice Told The Poisoners mh-13

The Poisoners mh-13 The Ambushers

The Ambushers Death of a Citizen mh-1

Death of a Citizen mh-1 The Silencers

The Silencers The Removers

The Removers The Intimidators

The Intimidators The Damagers

The Damagers The Menacers mh-11

The Menacers mh-11 The Retaliators

The Retaliators Murderers' Row

Murderers' Row The Ravagers

The Ravagers The Ravagers mh-8

The Ravagers mh-8 The Threateners

The Threateners The Betrayers mh-10

The Betrayers mh-10