- Home

- Donald Hamilton

The Wrecking Crew Page 10

The Wrecking Crew Read online

Page 10

“Yes,” I said. “That’s right. Pretending. I had some thought of keeping this strictly business.”

“That,” she said, coming forward, “was a very silly idea, wasn’t it?”

16

This was the land of the Midnight Sun, and while it was past the season for that particular display—it happens only around midsummer—the evenings were still late and the mornings were still early. Presently the long winter night would descend over the land, but not quite yet. It seemed very soon that there was light at the window.

She said, “I’d better get back to my room, darling.”

“No hurry,” I said. “It’s early, and the Swedes are a tolerant people, anyway.”

She said, “I was awfully lonely, darling.” After a while she said, “Matt?”

“Yes?”

“How do you think we ought to run this?”

I thought that over for a moment. “You mean, like strictly for laughs?”

“Yes. Like that, or like some other way. How do you want it?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “It’ll take some thought. I haven’t had too much experience along these lines.”

“I’m glad. I haven’t, either.” After a little, she said, “I suppose we could act cool and sophisticated about the whole thing.”

“That’s it,” I said. “That’s me. Cool. Sophisticated.”

“Matt.”

“Yes.”

“It’s a lousy business, isn’t it?”

She shouldn’t have said that. It admitted everything, about both of us. It gave everything away, and we’d been doing fine. It had been a smooth, polished act on both sides, one move leading to the next without a stumble or a missed cue; and then, like a sentimental amateur, she went and deliberately tossed the whole slick routine overboard. Suddenly we weren’t actors any longer. We weren’t dedicated agents, either, robots operating expertly in that kind of unreal borderland that exists on the edge of violence. We were just two real people without any clothes on lying in the same bed.

I raised my head to look at her. Her face was a pale shape against the whiter pillow. Her dark hair was no longer brushed smoothly back over her small, exposed ears. It was kind of tousled now, and she looked cute that way. She was really a hell of a nice-looking girl, in a slim and economical sort of way. Her bare shoulders looked very naked in the cold room. I pulled up the blanket and tucked it around her.

“Yes,” I said, “but we don’t have to make it any lousier than necessary.”

She said, “Don’t trust me, Matt. And don’t ask me any questions.”

“You took the words right out of my mouth.”

“All right,” she said. “As long as we both understand.”

I said, “You’re green, kid. You’re real smart, but you’re an amateur, aren’t you? A pro wouldn’t have given it all away like you just did. She’d have left me guessing.”

She said, “You gave yourself away, too.”

“Sure,” I said, “but you knew about me. You’ve known about me all along. I still wasn’t quite sure about you.”

“Well, now you know,” she said, “something. But are you sure what?” she laughed softly. “I really have to go. Where’s my dress?”

“I don’t know,” I said, “but there seems to be somebody’s brassiere hanging on the foot of the bed.”

“The hell with my brassiere,” she said. “I’m not going to a formal reception, just across the hall.”

I lay and watched her get up and turn on the light. She found her dress on a chair, shook it out, examined it, pulled it on, fastened it up, and stepped into her shoes. She went to the dresser, looked at herself in the mirror, and pushed helplessly at her hair. She gave that up, and came back to the bed to gather up the rest of her clothes. “Matt.”

“Yes?”

“I’ll double-cross you without blinking an eye, darling. You know that, don’t you?”

“Don’t talk so tough,” I said lazily. “You’ll scare me. Reach in my right pants pocket.”

She glanced at me, picked up my pants, and did as I’d asked. She fumbled around among some change and came out with the knife. I sat up, took it from her, and did the flick-it-open trick. Her eyes widened slightly at sight of the sharp, slender blade.

“Meet Baby,” I said. “Don’t kid yourself, Lou. If you know anything about me at all, you know what I’m here for. It’s in the open now, that’s all. This doesn’t change anything. Don’t get in my way. I’d hate to have to hurt you.”

We’d had a moment of honesty, but it was slipping away from us fast. We were starting to hedge on our bets. We were falling enthusiastically into our new roles as star-crossed lovers, a jet-age Romeo and Juliet, on opposite sides of the fence. Too much frankness can be as much a lie as too little. Her speech about double-crossing had been unnecessary; she’d already warned me not to trust her. If you say “Don’t trust me, darling” often enough, you can make the warning lose its effect.

As for me, I was brandishing a knife and making bloodcurdling speeches: good old bone-headed, fist-fighting Secret Agent Helm flexing his muscles before a lady he’d just laid.

I think we both felt a kind of sadness as we looked at each other, knowing we were losing something we might never find again. I closed the knife abruptly and tossed it on top of my pants on the chair.

She said, “Well, I’ll see you at breakfast, Matt,” and leaned over to kiss me, and I put my arm about her just above the knees, holding her by the bed. “No, let me go, darling,” she said. “It’s getting late.”

“Yes,” I said. “Have you seen yourself like that?”

She frowned. “You mean my, hair? I know it’s a mess, but whose fault—”

“No, I don’t mean your hair,” I said, and she looked down at herself quickly, where I was looking, and seemed a little startled to see the way her unconfined breasts made themselves quite obvious through the clinging wool jersey of her dress. It was the same elsewhere. It was really quite a thing: the simple, discreet black dress with its party touch of satin at the waist and so obviously nothing but Lou inside it. She’d have been much more respectable in a transparent negligee.

She murmured, rather abashed, “I didn’t realize… I look practically indecent, don’t I?”

“Practically?”

She laughed, and shaped the black cloth to her breasts with her hands, a little defiantly. “They’re kind of small,” she said. “I always wondered if any other animal besides man... I mean, do you think bulls, for instance, go for the cows with the biggest udders?”

“Don’t be snide,” I said. “You’re just jealous.”

“Naturally,” she said. “I’d just love to have them out to here… well, I guess I wouldn’t, really. Think of the responsibility. It would be like owning a couple of priceless works of art. This way, I don’t have to spend my life living up to them.”

I said, “If current fashions continue, I suppose we’ll eventually wind up with a whole race of skinny women with giant tits.”

She said, quite primly, “I think the discussion has gone far enough in that direction.”

She was a funny girl. “Do you object to the word?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said, and tried to free herself again. “And I don’t really want to go to bed with you again right now, certainly not with my one good dress on, so please let me… Matt!”

I’d pulled her down on top of me. “You should have thought of that—” I said, rather breathlessly, as, holding her in my arms, I reversed our positions by rolling over with her—“you should have thought of that before you started looking so goddamn sexy.”

“Matt!” she wailed, struggling ineffectually among the bedclothes. “Matt, I really don’t want… Oh, all right darling,” she breathed, “all right, all right, just give me a chance to kick my shoes off, will you, and please be careful of my dress!”

17

Later, alone in the room, I shaved and dressed and organized my equipment for

the day’s shooting. I mean, it would have been nicer to spend a few lazy hours thinking about nothing but love, but it just wasn’t practical. As I was going out the door, I glanced back to see if I’d forgotten anything. Yesterday’s films, still lined up on the dresser, caught my eye.

I regarded them for a moment, a little grimly. Then I set my gear down, closed the door, and went over there. What I was thinking now seemed terribly suspicious and disloyal. She was a nice kid and she’d been, as sweet as she could be—but she’d also displayed some curiosity last night, maybe casual, maybe not, about just how and where I planned to get the stuff processed and printed.

Much as I hated to spoil what had happened between us with cynical afterthoughts, I couldn’t help remembering that I’d been playing it cool deliberately to see just what she’d do in the way of insuring my cooperation and lulling my suspicions. Well, she’d gone and done it, there was no denying that. Maybe she’d done it because she liked me, but one thing you learn very quickly in this business is not to take for granted that you’re just naturally irresistible to lonely women. Whatever her reasons, whatever her motives, she’d certainly allowed the businesslike relationship between us to be changed into something considerably more intimate.

I couldn’t afford to ignore the warning, or her display of curiosity about the films. It might mean nothing, of course, but I had to consider the possibility, at least, that these pix and the others I’d be taking in her company might have more significance than appeared on the surface. A few simple precautions seemed in order.

I sighed for my lost faith and innocence, went to the closet, and got out one of the metal .50-caliber cartridge boxes I use for preserving my main film supply. I dug out five unexposed rolls of Kodachrome and three unexposed rolls of black-and-white, still in the factory cartons. I sat down on the bed and opened the virgin film cartons carefully, breaking loose the adhesive with my knife without tearing the cardboard flaps.

Then I removed the unexposed films inside and carefully substituted the exposed films from the dresser. I glued the cartons shut again with patent stickum from my repair kit, and made a tiny identifying mark on each of the doctored cartons—a dot in the loop of the “a” in Kodak, if you must know—and buried all eight of them at the bottom of the box of fresh film, hoping I wouldn’t grab one by mistake some day when I was in a hurry.

I turned to the new films, and drew each five-foot film strip completely out of its metal cartridge, exposing it to light so that, if developed, it would turn totally black. No one would ever be able to determine whether or not it had ever held a real photographic image. There’s nothing as permanent and irrevocable as fogging a film, except killing a man.

I rolled all the films back into the cartridges by hand, got an empty camera, and one by one loaded them into the instrument, wound them a little way, and rewound them again. This gave the proper reverse curl to the leaders, as if they’d actually been used. I was getting pretty tricky now, but there’s no sense pulling a gag like that unless you make it good. I marked each fogged roll with an authentic-looking number to correspond with the data in my notebook. Finally I put the film cartridges in a neat row on the dresser, where they looked exactly like the films that had stood there before.

Probably I was just wasting my time. However, I had plenty of film to spare, and if I was wrong there was little harm done. It seemed about time to start taking a few obvious precautions, anyway. I had to remember that the opposition had tested me carefully at least once and maybe twice—if little Mr. Carlsson wasn’t exactly what he’d claimed to be. They’d found me stupid and harmless enough to let live, while Sara Lundgren had been killed. The difference was, presumably, that they had no further use for her, while they needed me for something.

I still didn’t know with certainty what that something was. However, if yesterday was a reliable indication, I was going to be taking a lot of pictures in this northern country—and I was going to be taking them under the very close supervision of a young lady whose motives weren’t exactly clear, to put the matter with the greatest charity possible. It seemed just as well to make reasonably sure of retaining control of my pix until I could determine that everything I’d been told to photograph was completely innocuous. Not that it had much bearing on my primary job—Mac wouldn’t give a damn what happened to my films—but I do take a certain pride in my photography, and I wasn’t going to let it be used, unnecessarily, for purposes of which I didn’t approve.

Finished, I crossed the hall and knocked on Lou’s door. “I’m going downstairs,” I called. “See you in the dining room.”

“All right, darling.”

The endearment made me feel like a calculating and suspicious beast, but one of the things you have to keep in mind in this work is that what happens in bed, no matter how pleasant it may be, has no bearing on what happens anywhere else. A woman may be sweet and wonderful under those circumstances, and still be dangerous as a rattlesnake with her clothes on. Cemeteries are full of men who forgot this basic principle.

When I crossed the small lobby, there was a girl speaking to the clerk at the desk. My interest in stray females was at a low ebb that morning, for reasons both emotional and glandular, and this one was wearing pants—bright plaid pants at that—so I didn’t even bother to examine her rear view closely as I headed for the dining-room door. Her voice caught me by surprise.

“Good morning, Cousin Matthias.”

I swung around to face Elin von Hoffman. That kid could do the damndest things to herself and still be beautiful. This morning, in the loud pants and a heavy gray ski sweater, without a trace of makeup besides that lousy lipstick she’d worn the night before, she was still something to make you weep for your wasted life. She held out a small key by its tag and chain.

“I brought your car,” she said. “Those old Volvos are not much good, are they?”

“It runs,” I said. “What do you expect for thirty crowns a day, a Mercedes 300SL?”

“Oh, you know sports cars?” she asked. “In Stockholm I have a Jaguar, from Britain. It is very handsome and exciting. I also have a little Lambretta which is much fun. That is a motor scooter, you know.”

I said, “Yes. I know.”

She laughed. “I am still trying to educate you, aren’t I? Well, I must go.”

“I’ll drive you,” I said.

“Oh, no. That is why I came, for the walk back. I love walking, and it is such a fine day.”

“It looks kind of gray and windy to me.”

“Yes,” she said. “Those are the best.”

So she was one of the rain-in-the-face kids. Well, she’d outgrow it; she had plenty of time. I said, “That’s a matter of taste. Like walking.”

“You say you like hunting. If you hunt, you must walk.”

“I’ll walk if I can’t get a horse or a jeep,” I said. “I don’t mind a little hike, if there’s a chance of a shot at the end of it. But not just for the sake of hiking.”

She laughed again. “You Americans! Everything must show a profit, even walking… Good morning, Mrs. Taylor.”

Lou had come down the stairs, in her working uniform of skirt and sweater and trench coat. Beside the taller, younger Swedish girl in her outdoor clothes, she looked surprisingly slight, almost fragile, although I had good reason to know that she didn’t break easily. The thought, for some reason, was a little embarrassing at the moment. I saw the kid look from Lou to me and back again. She was young, but not that young; she saw something and understood it. I guess it usually shows, except on the really hardened sinners, which we were not. When Elin spoke again, there was noticeable stiffness in her voice.

“I was just leaving, Mrs. Taylor,” she said. “Good-bye, Herr Helm. Your car is in the parking space across the street.”

We watched her go out the door into the gray fall morning. The wind caught her hair as she came outside, and she brushed it out of her face, and tossed it back with a shake of her head, and went out of sight with the e

fficient, no nonsense stride of the practiced foot traveler, that you hardly ever see in America nowadays. Come to that, America never was much of a country for walkers and runners, at least after the frontier hit the Great Plains. There was just too damn much ground to cover efficiently on foot. Most of the old-timers sensibly preferred to ride. There are some real fancy foot pilgrimages on record, but if you check closely you’ll find that in almost every case they start with a horse getting killed or stolen. Walking for fun is strictly a European custom.

“Who is that overgrown child?” Lou asked as we went on into the dining room. “I never got her name straight last night.”

“Child yourself, honey bunch,” I said. “From my advanced age, twenty-two doesn’t look much younger than twenty-six.”

“Well, you ought to know, grandpa,” she said, smiling. “You were right in there looking, at dinner last night.”

I seated her at a table by a window. “My interest was purely aesthetic,” I said firmly. “I was admiring her as a photographer. You must admit she’s so beautiful it hurts.”

“Beautiful!” Lou was shocked. “That gawky—” She stopped abruptly. “Yes, I see what you mean. Although I don’t go for the nature-girl type myself.” She grimaced. “You hear about Sweden being such an immoral country; how do they manage to grow up with that damn dewy look? I never looked like that, and I can tell you, I was innocent as hell practically to the day I married.”

“Practically?” I said.

She smiled at me across the table. “Don’t be nosy. If you must know, Hal and I anticipated the ceremony slightly. As he put it, you wouldn’t buy a car without driving it around the block, would you?”

“Nice, diplomatic Hal,” I murmured.

She said, “Oh, I didn’t mind. I… learned a lot from Hal. He was pretty conceited, sometimes, and he couldn’t always be bothered with being kind, but we both knew he needed me. He was a strange person, very brilliant, but temperamental and erratic. Sometimes I wondered if... you know, I wasn’t quite sure that I really meant anything to him except, well, a convenience. But you can forgive a man a great many things, Matt, when the last thing he does, with a machine gun spitting in his face, is to turn and do his best to protect you with his body. He saved my life, remember that.”

The Two-Shoot Gun

The Two-Shoot Gun Mad River

Mad River Texas Fever

Texas Fever Ambush at Blanco Canyon

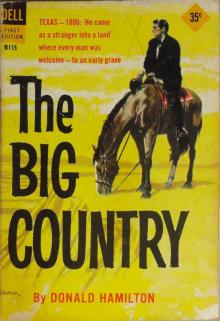

Ambush at Blanco Canyon The Big Country

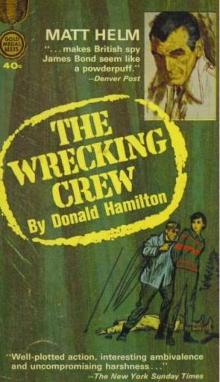

The Big Country The Wrecking Crew

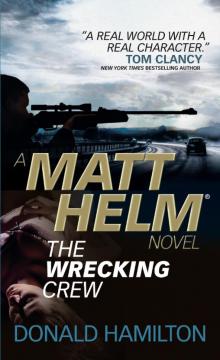

The Wrecking Crew The Devastators mh-9

The Devastators mh-9 The Wrecking Crew mh-2

The Wrecking Crew mh-2 The Shadowers mh-7

The Shadowers mh-7 The Ambushers mh-6

The Ambushers mh-6 The Betrayers

The Betrayers The Terrorizers

The Terrorizers The Poisoners

The Poisoners The Devastators

The Devastators The Silencers mh-5

The Silencers mh-5 The Interlopers mh-12

The Interlopers mh-12 The Shadowers

The Shadowers The Annihilators

The Annihilators The Vanishers

The Vanishers Night Walker

Night Walker The Revengers

The Revengers The Frighteners

The Frighteners The Infiltrators

The Infiltrators The Intriguers mh-14

The Intriguers mh-14 The Steel Mirror

The Steel Mirror The Menacers

The Menacers Assassins Have Starry Eyes

Assassins Have Starry Eyes Death of a Citizen

Death of a Citizen Matt Helm--The Interlopers

Matt Helm--The Interlopers The Removers mh-3

The Removers mh-3 The Demolishers

The Demolishers Murder Twice Told

Murder Twice Told The Poisoners mh-13

The Poisoners mh-13 The Ambushers

The Ambushers Death of a Citizen mh-1

Death of a Citizen mh-1 The Silencers

The Silencers The Removers

The Removers The Intimidators

The Intimidators The Damagers

The Damagers The Menacers mh-11

The Menacers mh-11 The Retaliators

The Retaliators Murderers' Row

Murderers' Row The Ravagers

The Ravagers The Ravagers mh-8

The Ravagers mh-8 The Threateners

The Threateners The Betrayers mh-10

The Betrayers mh-10