- Home

- Donald Hamilton

Texas Fever Page 6

Texas Fever Read online

Page 6

CHAPTER 10

They turned the herd westward. There was some discussion of turning east, bypassing Kansas in that direction, but other herds had tried that route in previous years, and stories of their hardships in the flint hills of Missouri had filtered back to Texas. Better to go a little farther and keep the cattle in good condition, than to reach market with a herd of sorefooted ambulating skeletons.

The following evening a little man came riding into camp on a fine tall bay that had a thoroughbred look. The rider was well dressed, but he wasn’t much of a horseman; it was a good thing there wasn’t much weight to him, Chuck thought, or that fine horse would have had a mighty sore back, the way he bounced around in the saddle. He asked for the man in charge and was invited to partake of food and coffee while he waited for the Old Man to return from his nightly scout. He accepted the coffee but refused the food—after a shocked look at the evening’s greasy stew—which didn’t endear him to the cook, or to anybody else in the outfit, for that matter. It was all very well for them to complain about the fare, but for a stranger to spurn it was an insult to everybody.

Presently the Old Man came riding in, and the two of them went around behind the wagon, the little man talking while the Old Man ate his supper. Chuck couldn’t hear what was being said, and he didn’t want to seem to be eavesdropping, so he busied himself wiping off his pistol and fixing his bedroll for the night, but he was thoroughly aware when the Old Man came back into sight with his empty tin plate and cup, to toss the plate into the cook’s pan of water and fill the cup with fresh coffee. The little man was following him with the impatient, frustrated look of one who’d talked himself out against another man’s silence.

“Well, Major McAuliffe?” he demanded.

The Old Man looked down at him and spoke deliberately: “Before I sell these cattle at your price, sir, I’ll slaughter them for their hides. Good day.”

The little man started to speak angrily, but checked himself. He strode to his handsome horse, reached the saddle after three tries, and rode off with his coat-tails flapping. That night, half a dozen unidentified riders tried to stampede the herd, but the Old Man had the whole crew awake and the attackers were driven off without damage.

The next day, and the day after that, they moved westward. On the morning of the fourth day they turned north again, crossed the Kansas line—as near as they could figure—and, on the following morning made some six miles before they were stopped by grim men bearing shotguns and pitchforks, accompanied by an officer of the law who threatened to throw them all in jail and confiscate the cattle if they weren’t out of the state by nightfall. That evening, an unctuous personage who had the look of a banker drove up in a shabby buggy that had the look of a livery-stable rig and offered to buy the herd at two dollars a head, saying that he was a kindly man who couldn’t bear to think of their having come all the way from Texas for nothing. The Old Man threw him out.

Back in Indian Territory, they continued to the west. They had a week of good weather, but nobody appreciated it much, heading in the wrong direction. Tempers grew strained; even the Old Man grew snappish and sarcastic, like he’d been right after his return from the war. One evening he came riding into camp after being gone most of the day, and summoned Chuck and Joe Paris to him.

“Well, there it is,” he said with a jerk of his head, after tasting his coffee and spitting it out. “Coosie, for the love of God,” he said turning his head, “why don’t you wash your dishrag in the other pot?”

The cook came hurrying to take the cup and refill it, something he’d have done for no one else in the crew. When he was gone, Chuck asked, “What’s there, sir?” “Jepson, Kansas, of course. The town your lady friend was so careful to impress upon your memory!”

Chuck flushed and was silent. Joe Paris asked, “How far?”

“Just across the line, near as I can figure, about a day’s drive west.”

Joe said, “We’d better give the place a wide berth. We’re not apt to find anything pleasant, following that young female’s advice.”

“No,” the Old Man said, “but we might find a murderer.”

There was a little silence. Jesse McAuliffe’s voice was grim; there was no laughter left in him now, Chuck saw. The past days of moving steadily away from their original destination, Sedalia, of butting repeatedly against that wall of armed hostility to the north, had taken their toll. There was the land of plenty, where cattle sold for twenty and thirty dollars a head, almost within reach, but always the way was barred.

“You think they’ll be there?” Joe asked.

Jesse McAuliffe moved his shoulders. “If they are, we’ll have gained at least that much. If they aren’t . . . Maybe there was some good in the girl, after all. Maybe she’d actually heard something and was giving us the benefit of it, in return for our having saved her man’s life. I put no real faith in it, but it’s worth a try. We aren’t getting any closer to the railroad this way, that’s for sure.”

“I don’t like it,” Joe said*

“Neither do I,” the Old Man said. “But I don’t like driving these cattle clear to Colorado, either.”

In the morning, they swung somewhat to the north, angling closer to the invisible line that marked the limit of Indian Territory. They drove all that day through open country with good grass and water. The longhorns were putting on weight, Chuck reflected; they’d be in fine shape to sell, if somebody was ever found to buy at a fair price.

They camped for the night by a small creek. In the morning they turned due north, moving into Kansas again. About noon, the Old Man, scouting ahead, came back into sight. As he approached he gave the signal to halt, while the low rise of ground behind him began to fill with men, more than they’d met anywhere before.

The Old Man’s face was bleak when he reached them. “It’s the same damn story,” he said. “There’s a young deputy sheriff back there says we’ve got to turn them around. Turn them and get them moving, he says, before he arrests the lot of us and impounds the herd.” “Moving’s fine,” Chuck said bitterly. “Did he happen to say where?”

His father shrugged. “Back into the Nations, I reckon. He said the local settlers have lost some stock to Spanish fever, and they don’t aim to let us infect any more with our diseased animals.”

Chuck felt impotent rage grip at his throat and chest “Diseased?” He looked towards the men on the ridge, and heard their jeering laughter. “I’d like to see a couple of those cackling sod-busters come down here on foot These poor diseased longhorns would soon make them laugh on the other side of their . . ."

He stopped, because his father wasn’t listening. He was regarding the herd, with an odd faraway look that made Chuck uneasy. He seemed to be debating something with himself. Deliberately, he dropped the tied-together bridle reins, removed his hat and hung it on the saddle horn, and wiped his forehead with a bandana handkerchief, performing each act in order with his single hand. Then he returned the handkerchief to his pocket and, still frowning at his cattle, put the hat back on his head, lost in thought.

Suddenly he looked up. Chuck followed the direction of his father’s glance, and saw that a large young man with a badge on his shirt was riding down the slope towards them—that would be the deputy the Old Man had mentioned. He was mounted on a big, awkward-looking gray. With him was another man, also mounted, if you could call it that. Some of these Yankees, Chuck reflected, didn’t seem to care much what they put under their saddles. Well, it wasn’t hard to understand, when you looked at the saddles. The two men reined in half a dozen yards away.

“The boys are getting impatient,” said the big young deputy, not much older than Chuck himself. He had the swaggering look some men got when you pinned a badge on them, and he wore a fine new revolver at his hip. “Your time’s about up, McAuliffe,” he said. “What’s it to be?”

Chuck heard his father draw a long, defeated breath. “We’ll move ’em,” Jesse McAuliffe said. “How far does this quarantin

e of yours run, anyway? Any way of getting clear around it?”

It was the other man who answered. “Not and reach the railroad, there isn’t, friend.”

The Old Man turned a strangely mild glance on this one, a long thin man in a shabby black suit and hat, whose eyes were hidden by the reflections of gold-rimmed spectacles. In contrast to his respectable clothes, his breath, even at a distance, carried the aroma of strong spirits.

“Who are you?” Jesse McAuliffe asked.

The deputy said, “This is Mr. Paine. He’s got a proposition for you.”

“So?” The Old Man didn’t take his eyes from the thin one. “Well, Mr. Paine?”

The man called Paine cleared his throat. It was long enough and knobby enough, Chuck thought, to take a bit of clearing; and the stiff collar surrounding it was far from clean. Paine said: “You won’t get this herd to Sedalia, friend, or any other point on the railroad. The quarantine line runs west of all of them. Oh, some of you Texans slipped through last year, and even a few this spring, but our good people are still paying the price in dead and ailing cattle. They’re not going to let it happen again; they’re ready to take to arms to prevent it, as you can see.”

The deputy nodded agreement. “As far as this county’s concerned, the sheriff’s given orders not to let a single head of Texas beef across the line. And I know the neighboring counties feel the same way.”

“I see,” the Old Man said. “You got any suggestions, friend?” He was still regarding the thin one steadily.

It was the deputy who spoke again, however, looking sourly at the nearest steer, tall and leggy, with a five-foot horn spread. “You call that a domestic animal?” he sneered. “As far as I’m concerned, you can take them all back to Texas, Mister. We don’t want them here.” The thin man with the eyeglasses said quickly, “However, there’s a reasonable solution to your problem, Major. It just happens that I have a contract to supply beef to a couple of Army posts to the west, outside the quarantine area. I’ll take tins herd off your hands, if the price is right.”

Chuck saw his father’s eyes narrow. “And your idea of a suitable price, sir?”

There was a little pause. Paine looked at Jesse McAuliffe and raised his head to let his small, veined eyes, behind the spectacles, sweep the herd appraisingly. “They’ve come a long ways. I’d have to fatten them up a bit before the Army’d take them. Three dollars.”

Jesse McAuliffe’s voice was soft and lazy. “Three dollars a head, sir, or three dollars for the entire herd?” Paine flushed at the sarcasm. “Three dollars a head is my offer. . . . Yes, yes, friend, I know they’re paying around twenty at the railroad, but the Army won’t pay me that, and you’re not at the railroad. Nor are you likely to get there. Think it over, friend, but don’t think too long. Yours isn’t the only herd that’s been turned back. I wouldn’t have to ride very far to find half a dozen Texas outfits marking time below the line, hoping for the quarantine to be lifted. Well, it won’t be. . . . I suggest you return to the creek where you camped last night. I’ll be over tomorrow morning for your answer. Come on, Reese.”

Chuck watched the two men ride away. Their horsemanship, he decided, was just about up to the standard set by their saddles and horseflesh. He didn’t want to look at his father and see that look of defeat in the Old Man’s eyes. It had been there right after the war, he remembered, but it had faded gradually. Now it was back.

CHAPTER 11

Jessie McAuliffe rubbed the stump of his left arm absently. He was staring towards the men on the rise.

“Chuck,” he said quietly, “your eyes are younger than mine, boy. Look to the right. See anyone you know?”

Chuck stared at the silhouetted figures. He frowned abruptly, seeing a bearded figure on horseback a little to the rear.

“Why,” he said, “it looks like Mr. Netherton . . ."

But his father had already swung his pony around, and was riding southwards along the edge of the herd. Chuck rode after him; and Joe Paris and the other riders, sensing that something was up, left their posts to converge upon the two of them. Jesse McAuliffe looked back once, as if to orient himself, at the noisy jeering crowd waiting on the brow of the rise. He rode until he had the herd squarely between himself and their position. Then he pulled up and let the crew gather about him.

He said to Joe Paris: “See him?”

Joe nodded. “The man must be tough. I didn’t think he’d be in shape to ride yet.”

The Old Man said, “Boys, those Yanks are getting real impatient for us to move.” He looked hard at the little group of riders about him. Chuck saw that his father’s pale blue eyes were suddenly very bleak and bright in his weathered face, stubbled with gray-white beard after the long weeks on the trail. Jesse McAuliffe reached down and pulled the Colt revolving pistol from its holster at his hip. “Let us oblige the gentlemen,” he said softly. “Let us move these here diseased three-dollar cattle!”

Chuck, not quite comprehending his father’s meaning, looked at the other men. He saw the sudden hard, bright look of excitement in their faces. It was the look of men just a little too familiar with lost causes; of men, like his father, turned a little mad by the sting of everlasting defeat.

Jesse McAuliffe’s big pistol swung up and fired at the sky. Joe Paris laughed suddenly and whipped out his revolver and pulled the trigger. Somebody howled like a wolf, and the herd broke. One moment, the longhorns were still standing there, wary but motionless; the next moment they were off with a sound like sudden thunder, with the crew after them, fanning out to guide them and urge them along. Chuck caught sight of his father’s gray coat disappearing into the dust downwind of the herd. He sent his pony after it, drawing the cap-and-ball Remington. The dust enveloped him.

He heard a gunshot ahead, dim above the sound of the stampeding cattle. Somewhere close by in the dust, Joe Paris howled like a coyote baying at the moon—for all his dry, middle-aged look, there was a streak of wildness in the man. The coyote-howl was answered by the high and quavering rebel yell from up ahead: that was the Old Man himself cutting loose. The excitement was contagious: Chuck raised his pistol and fired at the sky.

“Run, you Texas jackrabbits!” he yelled at the steers looming out of the dust on,his left. “You’ve been craving it, now run your fool heads off!”

He felt his pony begin to labor as the ground rose before them. Then he was out of the dust again, close behind his father, with Joe Paris pulling alongside to the right. Ahead was the mob, what was left of it. Most of the Kansans were scrambling for safety, but a couple still stood staring in petrified disbelief at the onrushing river of longhorned cattle. Then these men, too, broke and ran. As the stampede rolled over the deserted crest of the hill, a shot sounded from the right and behind, and Jesse McAuliffe dropped his revolver and went slack in the saddle.

Chuck threw a glance over his shoulder. The big deputy sheriff was there, riding in at an angle on his clumsy gray. His face was contorted with anger, and he had his fine new revolver in his hand; but one shot was all the plug intended to stand for, and the deputy was having has hands full.

Ahead, Joe Paris had raced alongside the Old Man, whose coat was already dark and wet from the shoulder-blade down. Chuck heard a bullet go overhead, whether aimed at him or the older men ahead, there was no telling. He reined his pony around sharply, but the dust closed in again, and he could see no target. Then the big gray, terrified by the shooting, running wild and uncontrollable, came charging out of the murk right on top of him, and horses and men went down together.

Rolling free of the tangle, Chuck came to his feet. He found that he still had his revolver in his hand. The deputy was crawling around on hands and knees, scratching at the ground dazedly: Chuck realized that he was groping for his own gun, which was nowhere to be seen. Chuck raised his weapon, but the sights kept blurring in a strange way, and he realized that blood was running down his face and his head felt very strange. He got a bead on the crawling figure of the other man,

and waited for the deputy to look around; somehow he couldn’t bring himself to fire at a man who wasn’t looking. But the deputy kept crawling the other way, and Chuck couldn’t be bothered with him any more. He shoved the pistol into its holster, turned, and stumbled through the dust to where Joe Paris was kneeling beside a figure on the ground.

As Chuck came up, Joe rose, his face saying everything that needed to be said. Chuck dropped heavily to his knees beside the Old Man, who opened his eyes. His lips moved.

“Sorry, boy,” Jesse McAuliffe whispered. “Man should never put off . . . Wanted to talk . . . tell you . . . thought we’d have more time . . . later . . . Never enough time,” he whispered. “Never enough time. . . .”

After a little, Chuck started to rise, but the world was rotating strangely about him, and the day seemed to be growing dark. He felt Joe Paris catch him as he started to pitch forward across his father’s body.

CHAPTER 12

He awoke in bed, with a throbbing headache. When he opened his eyes, he found the light painful, and quickly closed them again, but not before discovering that he was in a room with flowered wallpaper, smooth and clean, and crisp white curtains at the windows. It had been a long time since he’d seen anything of the sort.

Somebody left the room and said, outside the door,

“He’s awake now, Dad.” It was the voice of a girl or young woman. He’d never heard it before.

A man answered her out there: “All right, honey.” Booted feet came through the door and approached the bed. Chuck opened his eyes again, and looked up at the man standing over him—a compact, grayhaired individual of indeterminate age. He had the leathery, durable look that long exposure to the elements gives some men. Once they get it, around the age of thirty-five or forty, they don’t change much until they die. This man had gray eyes and a drooping gray mustache that partly hid his mouth. He wore a badge on his shirt.

The Two-Shoot Gun

The Two-Shoot Gun Mad River

Mad River Texas Fever

Texas Fever Ambush at Blanco Canyon

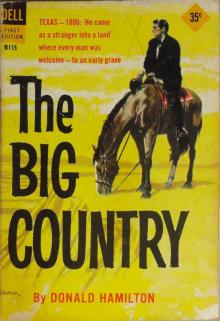

Ambush at Blanco Canyon The Big Country

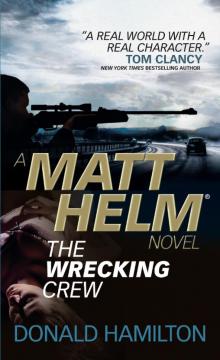

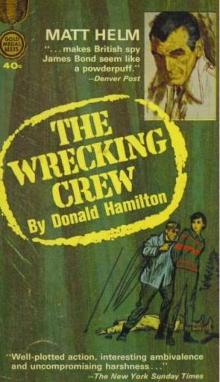

The Big Country The Wrecking Crew

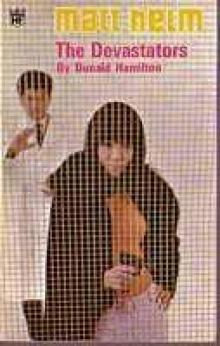

The Wrecking Crew The Devastators mh-9

The Devastators mh-9 The Wrecking Crew mh-2

The Wrecking Crew mh-2 The Shadowers mh-7

The Shadowers mh-7 The Ambushers mh-6

The Ambushers mh-6 The Betrayers

The Betrayers The Terrorizers

The Terrorizers The Poisoners

The Poisoners The Devastators

The Devastators The Silencers mh-5

The Silencers mh-5 The Interlopers mh-12

The Interlopers mh-12 The Shadowers

The Shadowers The Annihilators

The Annihilators The Vanishers

The Vanishers Night Walker

Night Walker The Revengers

The Revengers The Frighteners

The Frighteners The Infiltrators

The Infiltrators The Intriguers mh-14

The Intriguers mh-14 The Steel Mirror

The Steel Mirror The Menacers

The Menacers Assassins Have Starry Eyes

Assassins Have Starry Eyes Death of a Citizen

Death of a Citizen Matt Helm--The Interlopers

Matt Helm--The Interlopers The Removers mh-3

The Removers mh-3 The Demolishers

The Demolishers Murder Twice Told

Murder Twice Told The Poisoners mh-13

The Poisoners mh-13 The Ambushers

The Ambushers Death of a Citizen mh-1

Death of a Citizen mh-1 The Silencers

The Silencers The Removers

The Removers The Intimidators

The Intimidators The Damagers

The Damagers The Menacers mh-11

The Menacers mh-11 The Retaliators

The Retaliators Murderers' Row

Murderers' Row The Ravagers

The Ravagers The Ravagers mh-8

The Ravagers mh-8 The Threateners

The Threateners The Betrayers mh-10

The Betrayers mh-10