- Home

- Donald Hamilton

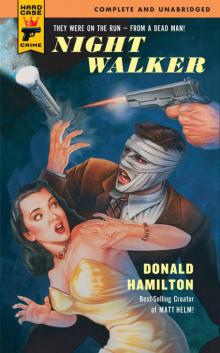

Night Walker Page 5

Night Walker Read online

Page 5

Chapter Six

The remainder of that day was a jumble of confused impressions with which Young did not try to cope, taking refuge in sleep, real or pretended. Then, suddenly, it was morning again, he was alone in the sunlit bedroom, and his mind was refreshed and clear. He could no longer avoid the thought that was clamoring for his attention.

“Deserter,” he whispered, fitting the ugly word to his tongue. This was the real edge to Dr. Henshaw’s threat. The notion of being accused of murder was too unreal to be taken quite seriously; but this was a charge that he could not honestly deny, remembering his indecision in the hospital, and his readiness here to play the role Elizabeth Wilson had desired of him. He might never have consciously decided not to report for duty; but he had certainly been quick enough to lose himself in another man’s identity when the opportunity offered.

Yet the idea had a fantastic quality; it was something he had never considered, even back in the bad days after his release from the hospital when it had seemed they were about to send him back to sea again. He had considered throwing himself on the mercy of the medical authorities, and he had on one occasion toyed with the thought of shooting himself, but it had never occurred to him to think of deserting. The war’s end had saved him then. When, a few weeks ago, he had received orders back to active duty he had gone out and got thoroughly plastered, but he had not dreamed of not proceeding and reporting as ordered. Yet the germ of the notion must have been somewhere in his mind, he reflected, for him to slide so readily into acceptance of the present situation....

He sat up abruptly. Acceptance, hell! he thought, with sudden anger. Listening, he could hear sounds of activity from the kitchen downstairs, but nothing moved on the second floor of the house. He threw the covers aside, swung his feet to the floor, and stood up cautiously. The problems of operating in a vertical rather than a horizontal plane took a little consideration, but he ventured the three steps from the bed to the dresser without meeting disaster. From there he made it to the nearby closet door. Opening this, he studied the clothes inside. There were not very many of them; apparently Lawrence Wilson had removed most of his personal belongings when he left. Nevertheless, enough remained to dress his successor adequately; and it had already been established, Young reflected, that Wilson’s garments would fit him. After all, he had been wearing one of the man’s suits when the police had picked him up, half dead, at the scene of the wreck.

He frowned, his mind busy with feverish plans for escape. He was not aware of the girl’s presence until her soft, Southern voice addressed him from the doorway.

“Honey, whatever are you doing? You’re supposed to stay in bed, hear?”

He turned, startled, to face her. She was wearing the somewhat tarnished gold robe that seemed to be her usual morning costume, and her dark hair was no tidier than it had been the morning before, but her mouth was red with fresh lipstick. She was holding a large tray with breakfast for two. When he did not move or speak, she came forward and set the tray on the dresser. She looked up at him, standing there.

“I declare, you’re bigger than I remembered. It’s no wonder we had trouble getting you up the stairs the other day.”

Her appearance and attitude disconcerted him. He found himself, unwillingly, aware of the graceful shape of her body beneath the satin negligee, and of the small, promising fullness of her lower lip. It was hard to look upon her as a jailer.

He said, “I can’t stay here, Mrs. Wilson.”

Her eyes widened slightly. “Why not?”

“The Navy’ll be looking for me.”

“Let them look, honey. They won’t come here. You’re Larry Wilson now, remember.”

He said, “That’s not precisely what I meant.”

She hesitated. “Oh, I see. You’ve changed your mind. You want to go back?” Her voice was flat. She glanced at the open closet door. “You were looking for some clothes to run away in, honey? That’s why you’re up?”

He nodded.

She regarded him for a moment longer, then said, “Why, you don’t have to run away, honey. The telephone’s right at the foot of the stairs. You can call them right now if you like. I declare, you’re big enough. I couldn’t do a thing to stop you. If you want to see me put in prison —” Her voice trailed away. She faced him a little defiantly, her shoulders square and her head well back.

There was, he told himself, no reason why he should consider this girl in making his decision. Yet it was an added complication, and beneath the weight of it his strength and resolve began to crumble. He found himself swaying a little, and steadied himself against the dresser; then Elizabeth Wilson was beside him, helping him back to the bed.

“You do what you think is right, honey,” she said breathlessly. “I declare, I wouldn’t want you to get into trouble on my account. And don’t pay any attention to Bob Henshaw and his threats, hear? He told me what he’d said to you yesterday and I was perfectly furious with him. I hope you don’t think I’d let him do anything like that, even to save me. If you feel you’ve got to — to sacrifice me to your conscience, honey, you just go right ahead.”

Her voice was sweet and wholly insincere, yet her nearness was pleasant and reassuring. He caught her arm as, after tucking the covers about him, she started to rise. She stopped talking and looked down at him quickly.

He said, “Elizabeth, you’re a fraud. If I went near that phone, you’d probably shoot me.”

The false cheerfulness slipped from her face like a mask, leaving it strained and pleading. “But you won’t,” she whispered. “You won’t, will you, honey? You’ll stay and help me. Won’t you?” she whispered, and abruptly she raised a hand to her mouth and scrubbed it back and forth roughly, removing the fresh lipstick; then she kissed him without caution or restraint.

He was aware of the disturbing pressure of her lips and body; and he was not too weak to react to it, but she slipped away from him expertly as he tried to hold her, and stood up to look down at him, smiling. The smile gradually died away; and they studied each other for a long moment curiously, both clearly quite aware that a pact of sorts had been sealed.

“I declare,” she said, “it would be real nice if I could see your face.”

He said dryly, “Don’t be too sure of that.”

She moved her shoulders in a shrug that was less graceful than her usual gestures. “Well,” she said, “well, we’d better do something about this breakfast before it gets stone cold.”

He watched her turn toward the tray, the worn and soiled satin of her negligee swirling in a fluid way about her. He found that he could no longer look at her critically. They had suddenly become partners, accomplices in each other’s crimes.

He said abruptly, “It was during the war. I was on a ship that was torpedoed. Ever since I’ve been allergic to ships and the sea and fire and the smell of gasoline. I’ve tried to lick it, but every time I think I’m getting somewhere it comes back again, as strong as ever. Hell, after my little encounter with your husband, I wound up having one of my nightmares again. I hadn’t had one of those for four years.”

She brought him a plate and set a cup of coffee beside him. “You don’t have to tell me, honey. I declare, the uniform doesn’t mean anything to me. I saw too many of them in Washington during the war, and the fellows inside them all had the same idea, about me. That’s why I finally married Larry, I reckon; he was the one man I went around with who didn’t have a uniform and couldn’t act as if he thought his commission entitled him to bedroom privileges from every girl in Washington.”

Young said, “It isn’t just being scared, Elizabeth, although God knows I’m scared enough. It’s — well, it’s like this. I’m a lieutenant now; and I’d be up for lieutenant commander pretty soon. Well, a lieutenant commander probably didn’t seem very much to you in Washington, but he can be a pretty big wheel on shipboard. And — well, I keep seeing myself on the bridge some dark night with the responsibility for a few million dollars worth of ship, maybe

, and the lives of several hundred men and suddenly something happens, anything... I don’t know what I’d do, Elizabeth. I used to know, but I don’t any more. I simply have no idea how I’d react. And I guess I really would just as soon not have to find out; I guess that’s what it all amounts to, why I didn’t tell them who I was in the hospital, why I let you and Henshaw bring me here.”

She said, “Honey, eat your breakfast. I don’t care, I tell you.”

He looked at her where she was sitting on the edge of the bed now, eating off her knee; and he saw that she really did not care. She was not that interested in him. The fact that he intended to help her was enough. He found himself wryly amused at the thought that his personal tragedy could mean so little to someone else.

After she had left the room to take the tray downstairs, he got out of the bed again and moved around it to the window and looked out at the river and the Bay. They looked much as they had the day before; it was another nice day, with the same southeasterly breeze, apparently the prevailing summer breeze in this area. Far out, a sailboat was heading toward him wing-and-wing on a course that would eventually bring it into the mouth of the river below the house. Young wondered idly if this was the boat he had seen putting out the day before; presently, as it approached, he decided that this was a somewhat smaller craft. Something about it seemed vaguely familiar, reminding him of the picture Lawrence Wilson had shown him just before knocking him out, of the sloop he, Wilson, had designed for the girl called Bunny. The guess was confirmed when the boat came close enough for him to see that the small, solitary figure in the cockpit had red hair.

Bunny held her course clear across the river mouth to the near shore before she smartly put her helm down, brought the jib across, and trimmed sheets for the upriver reach. A thirty-foot sloop was not much boat by Navy standards, but it was still several tons of wood and metal, and several hundred square feet of canvas; a handful for a girl to manage. Young grimaced slightly; he did not like competent, athletic young women, particularly around boats; they always seemed to have a compulsion to demonstrate that they were just as good as men, or a little better. The kid was obviously showing off right now.

As she sailed past the big power cruiser moored at the Wilson dock, Bunny looked up at the house above. She must have seen him watching her from the window, because she raised a hand in greeting. Young hesitated, but it seemed better to wave back, and he did. The white sloop pulled away up the river, showing him the name lettered in gold leaf across the stern transom, too small to be read without glasses at this distance. He frowned at it, disturbed by a memory he could not immediately place. Boats? he thought, and then, with sudden understanding: Of course! Boats!

A sound behind him made him turn, to see Elizabeth standing there, regarding him a little oddly.

“Well, I declare, you’re real friendly with the child!”

He glanced over his shoulder at the small white yacht now disappearing around the wooded point up the river, and he laughed. “What am I supposed to do when she waves at me, stick out my tongue? I’m supposed to be her old pal Larry Wilson, aren’t I?”

Elizabeth did not smile. “I wonder what she was doing out there at this hour of the morning.”

“Just sailing around, I guess,” Young said, and dismissed the subject. “Tell me,” he said, “where’s that wallet?”

“What?”

“The wallet. Your husband’s wallet. I had it in the hospital, with his keys and some other stuff. Where did it get to?”

“Why, it’s in the top dresser drawer, honey,” Elizabeth said. “What—”

He moved past her to the dresser, pulled the drawer open, and took the pigskin wallet over to the bed, sitting down to examine it. Elizabeth seated herself beside him.

“What is it, honey?” she asked in a worried tone. “What are you looking for?”

“I just got an idea,” he said. He found the snapshot and looked at it for a moment. “What’s her name?” he asked curiously.

“Why, you know that,” Elizabeth said, surprised. “You called her Bunny yourself.”

“I hope she wasn’t christened that.”

“It’s really Bonita,” Elizabeth said; and somewhat tartly: “That’s a kind of fish, isn’t it?”

“You’re thinking of bonito,” Young said with a grin. “Bonita what?” As he asked the question, he remembered Dr. Henshaw’s reference to ‘the Decker girl’ the day before, but there was no need to admit that he had been eavesdropping.

“Bonita Decker,” Elizabeth said. “Honey, why are you so interested in her, all of a sudden?”

He said, with some annoyance, “Damn it, if I’m going to be Larry Wilson, I ought to know my girlfriend’s name, oughtn’t I? Don’t start spitting like a cat just because I ask a few questions. Actually, it’s the picture I’m interested in at the moment. Watch now!” He separated a corner of the snapshot from the backing that had been so neatly cemented to it, and stripped the two small rectangles of paper apart with a flourish. “I spotted this in the hospital, but it had slipped my mind. Now, what’s the name of the Decker girl’s boat?”

“Why, she calls it the Mistral, I think,” Elizabeth said, clearly puzzled by this performance. “But what—”

Young turned the photograph over, somewhat dramatically, to display the list of names written on the back. Her eyes widened with quick interest, and she leaned closer to look. They studied it together, Young paying particular heed, this time, to the lightly penciled notations opposite each name, that he had skipped over in examining the list hastily in the hospital while the nurse was out of the room.

Shooting Star, p, 28, N.Y.

Aloha, sl, 42, Newp.

Marbeth, p, 32, N.Y.

Chanteyman, k, 32, Jacks.

Alice K., sch, 40, Charleston

Bosun Bird, sl, 25, N.Y.

Estrella, p, 26, Wilm.

Presently Young drew a long breath and straightened up a little. “Well,” be said, “it isn’t there. No Mistral. So much for that idea. I don’t know what it would have proved anyway.”

Elizabeth glanced at him. “Honey, I don’t understand. What is it?”

“It’s obviously a list of boats,” he said. “With descriptions. Shooting Star, power boat, a twenty-eight footer, hailing from New York. Aloha, sloop, forty-two feet, Newport...‘k’ means ketch, I suppose, and ‘sch’ is schooner. Jacks is Jacksonville and Wilm is Wilmington. That much is pretty clear sailing, I think. But what the hell it means is something else again.” He frowned. “There’s a connection somewhere. Your husband spent a lot of time on that girl’s boat last summer, didn’t he? I got that impression from what he told me.”

“He certainly did!” Elizabeth’s voice was edged. “I declare, I never was so humiliated in my life. I wouldn’t — wouldn’t have minded so much losing my husband to another woman, but to a nasty child and a sailboat!”

Young glanced at her. It amused him to say, dryly, “According to him, you weren’t particularly eager to keep him after that Washington business.”

She flushed. “Well, I certainly wasn’t going to let anybody think I sympathized with his politics. But — but he didn’t have to go ahead and make a fool of himself in public, spending all hours of the day and night—”

“Maybe he wasn’t making quite such a fool of himself as you thought,” Young said.

She glanced at him quickly. “What do you mean?”

“Well, it’s got to tie in somehow,” Young said. “He gets fired from the Navy Department for subversive activities. He immediately goes to work on the Deckers’ boat, designing, building, and sailing the thing. Did he give any reason?”

She moved her shoulders briefly. “He said — I don’t remember exactly. Something about taking up yacht designing in a professional way, and this was a start. He said a designer can make his reputation on one good fast boat that wins a lot of races; and Mistral was going to be it, for him.”

“Did he need the money?”

<

br /> She shook her head quickly. “Heavens, no! There’s plenty of money, thank God; it’s the only thing that — that’s made my life here at all bearable, even before I learned — what he was doing.”

“You mean, he didn’t need his government job either?”

She shook her head again. “Oh, no,” she said. “He just started doing it during the war, and liked it; anyway, that’s what he said. He said having money is no excuse for a man’s sitting around on his can all day; that’s the way he put it. I believed him; why shouldn’t I have? It wasn’t until they fired him that I — that I began to think of little things that had happened, phone calls, people he’d go out to meet in the middle of the night... I didn’t want to turn against him when everybody else — But he didn’t need my help,” she said bitterly. “He didn’t want it. He had — her.”

Young said, “She’s just a kid.”

Elizabeth laughed. “Honey, she’s not that young; she graduated from college last spring. I declare, I feel kind of sorry for her. She’s a spoiled rich brat with a lot of wild political ideas; and she’s had a crush on Larry since she was in diapers. I’ve had to listen to heaven knows how many stories about the way she used to trail him around when they were kids; he was six years older, of course. I don’t think she knew what she was getting into; I think he sold her a bill of goods.”

The Two-Shoot Gun

The Two-Shoot Gun Mad River

Mad River Texas Fever

Texas Fever Ambush at Blanco Canyon

Ambush at Blanco Canyon The Big Country

The Big Country The Wrecking Crew

The Wrecking Crew The Devastators mh-9

The Devastators mh-9 The Wrecking Crew mh-2

The Wrecking Crew mh-2 The Shadowers mh-7

The Shadowers mh-7 The Ambushers mh-6

The Ambushers mh-6 The Betrayers

The Betrayers The Terrorizers

The Terrorizers The Poisoners

The Poisoners The Devastators

The Devastators The Silencers mh-5

The Silencers mh-5 The Interlopers mh-12

The Interlopers mh-12 The Shadowers

The Shadowers The Annihilators

The Annihilators The Vanishers

The Vanishers Night Walker

Night Walker The Revengers

The Revengers The Frighteners

The Frighteners The Infiltrators

The Infiltrators The Intriguers mh-14

The Intriguers mh-14 The Steel Mirror

The Steel Mirror The Menacers

The Menacers Assassins Have Starry Eyes

Assassins Have Starry Eyes Death of a Citizen

Death of a Citizen Matt Helm--The Interlopers

Matt Helm--The Interlopers The Removers mh-3

The Removers mh-3 The Demolishers

The Demolishers Murder Twice Told

Murder Twice Told The Poisoners mh-13

The Poisoners mh-13 The Ambushers

The Ambushers Death of a Citizen mh-1

Death of a Citizen mh-1 The Silencers

The Silencers The Removers

The Removers The Intimidators

The Intimidators The Damagers

The Damagers The Menacers mh-11

The Menacers mh-11 The Retaliators

The Retaliators Murderers' Row

Murderers' Row The Ravagers

The Ravagers The Ravagers mh-8

The Ravagers mh-8 The Threateners

The Threateners The Betrayers mh-10

The Betrayers mh-10