- Home

- Donald Hamilton

Murder Twice Told Page 3

Murder Twice Told Read online

Page 3

“Believe what?”

“… believe in what made you do it in the first place,” she whispered, her breath warm against his throat. “I’m glad you called them, Paul. I had to try to stop you, but I’m glad.”

She lifted her head to look at him. He gave her a large white handkerchief and watched her use it.

“That’s kind of a quick conversation,” he said quietly. “Marilyn, who do you think you’re kidding?”

Her voice was suddenly sharp. “What do you mean?”

He said, “You didn’t feel this way about it last night, when you made contact with me deliberately to tie me up tight with your lousy outfit. You aren’t going to claim you were trying to be inconspicuous in that little taffeta number, are you?”

She got slowly up from the bed without looking away from him.

He said, “As I see it, somebody needs me for something. This guy wanted to have something on me, so that if I balked at what he wanted me to do he could point out, oh, so politely, that I didn’t really have any choice. Who’s going to believe that I just happened to run into you in a bar last night? Or that I passed out on the sofa here, if that matters? After coming up here, what chance have I got to prove that I’m not part of the gang, particularly when a couple of witnesses can probably be supplied, if necessary, to testify that I’ve been working with them right along… Is that what you’re building up to, Marilyn, to confess everything to the F.B.I. including a couple of facts that don’t happen to be so?”

She said stiffly, “Go on.”

He said, “Well, that’s out now, Sweets. For the moment, I’m in the clear. I’m not your accomplice; I’m still an innocent bystander trying to act like a good citizen. Sure, I spent the night with a girl I used to know in Washington, but the minute I sobered up I remembered that she was wanted and reported her. You can’t turn me in, darling, because I’ve just finished turning you in. I’ve even offered to risk my life finding out what your game is. They don’t have to believe me—they probably don’t—but if they’re reasonably honest they’re going to treat me carefully until they can prove I wasn’t acting in good faith. As a matter of fact, the man I talked to more or less gave me authority to go ahead; he couldn’t very well refuse and have me claiming that they weren’t only persecuting me, they were even forbidding me to make any move toward finding evidence to clear myself.” He grinned without amusement. “So your boy friend hasn’t got anything on me. He can’t turn the screws and watch me squirm. I’m not part of his outfit unless I want to be; hell, I’m working for the government. So now I’m willing to listen to his proposition.”

He looked up at her, waiting for her to speak, and found himself realizing that you never really got over it: once you had been truly in love with a person, that person always retained a certain power over you. It was this, and not the reaction from being threatened with a gun, that had made him strike her, fighting against the knowledge that her kiss had stirred him in a way a hundred Jane Collises never would. It was this that was making him do his best to hurt her. It did not seem quite fair that he should have to sit there looking at a girl he had every reason to hate and feel disturbed by her thinness, worried by the small signs that kept cropping up to show that her nervous system had been taking a terrible beating. What was it to him if she was becoming bitter and disillusioned; did he want her to be really happy in the fine of work she had chosen for herself?

She said, quite softly, “I wouldn’t, Paul.”

“Wouldn’t what?”

“Whatever you’re trying to do. Either way, you’re double-crossing somebody—us or the others—and you’re not smart enough, or tough enough, to carry it through. Why, if you had what it takes to do that, you wouldn’t be sitting there looking ashamed of yourself every time you happen to notice the bruise on my face!”

He got up. “That’s all right,” he said. “I’ll struggle along as far as I get. Thanks for the advice, though.”

After a moment her shoulders, slender in the tailored blue robe, moved in a shrug. “Well, that takes care of my good deed for today. If you’ll get out of my bedroom I’ll get dressed now.”

He started to pass her without speaking. Making way for him, she seemed to stumble, her heel catching somewhere so that she fell against him. Then her arms were tight about his neck, holding him.

“Get out of here, you stubborn idiot! Who do you think you are, Dick Tracy? Get out, get out, get out!”

For a moment he believed her. Then, not quite sure that his first instinct had not been right, he knew that he could not take the chance: she could be only testing him. Something in her attitude had been calling for his attention, and he pushed her away and said deliberately, quite loudly:

“So the place is wired for sound. The only times you’ve dared talk straight is when you’ve had your mouth right up to my ear.”

Her face paled a little, and he saw her glance shift to the head of the bed, and back to him. She stepped back and drew herself up.

“That wasn’t a very nice thing to do to me,” she said quietly. “I was trying to help you.”

He said, “I remember how you helped me once. Let’s make with the phone, huh?”

IV

When he returned to the apartment house that evening, after going home to change, he could not find her name on any of the polished brass mailboxes in the lobby. He stood there, feeling helpless and quite ridiculous, until he remembered the apartment number. The engraved card in the slot opposite this number displayed the name of a Mrs. Elaine Susan Beckworth. He shrugged and pressed the button anyway, and the buzzer admitted him to the elevator. She had the apartment door open for him, and was in the living room mixing a drink when he came in. Her evening gown was of smoky blue-gray chiffon that seemed to drift about her quite weightlessly as she turned to greet him. He took the glass from her hand and examined her appearance critically, withholding his approval for a calculated time. Her eyes, he noticed, were a little too bright, and her cheeks were flushed; she must have had a couple of drinks alone while waiting for him. Or perhaps she had had other company while he was gone. He put aside the thought of the other men she must, in her business, have known—with an effort.

“You look as beautiful as in a dream I once had about you,” he said. Then he spoiled the compliment deliberately by glancing at his watch, which read almost eight-thirty. “Let’s get this over with, shall we?”

“We have plenty of time,” she said. “What happened? In the dream?”

He glanced at her. “When I tried to reach you, something fell on me. I woke up.”

“You made that up,” she said calmly. “You never dreamt that.”

“No,” he agreed. “But I might have, mightn’t I?”

After a moment she turned abruptly away from him, putting aside her half-finished drink. “Maybe we’d better go,” she said.

He watched her cross the room, knowing that he had hurt her. There was no satisfaction in the knowledge, any more than there had been in striking her. It was like getting mad and driving a fist at the wall. You could make a dent in the plaster, all right, but it was your own knuckles that bled. She waited for him at the apartment door. A length of the blue-gray chiffon was drawn about her otherwise uncovered shoulders like a fragile shawl, the ends passed through a small gold ring to hold them in front. She wore no other wrap.

“No coats?” he asked.

She smiled, deliberately mysterious. He shrugged and followed her into the elevator, and watched her push the button for the floor above. He thought he should have known it.

A tall man in dinner clothes was awaiting them on the seventh floor landing, the apartment door opened behind him. He was quite blond, balding, and there was a small scar under the corner of his right eye. For some reason the scar gave the impression of having been caused by the excessive kick, backfire, or explosion, of a rifle; perhaps because the man had a rifleman’s eyes. They looked at one object at a time, able to disregard everything else.

&n

bsp; Marilyn introduced the two men, and they shook hands. Weston made no attempt to match the other’s grip; it would not have done him any good to try.

“I’m very glad you could come, Mr. Weston,” said the man, whose name was Louis and, apparently, nothing else. “I’m always delighted to meet any friend of Elaine’s.”

Weston looked around for Elaine, a little startled, before he remembered the name on the mailbox downstairs. He reflected that Marilyn must have fun trying to keep her various identities apart. There was something childish about this business with names that gave him a little confidence. He murmured a polite phrase about being overjoyed, and Marilyn led them into the apartment, which was in all respects, even to the furniture, a duplicate of the one below. Only a few details were different: a hunting print in the place of a watercolor, a pipe rack and humidor in the place of a cigarette box and lighter. Beyond the archway that divided the living room from the dining room a table was elaborately set, waiting for them. A boy in a white coat was filling the water glasses.

Weston found himself a little puzzled by the whole performance; then he understood that these people, leading the lives they did, would naturally seize what opportunities they could to impress others with their polish and respectability: it was a form of compensation. Louis clapped him on the shoulder.

“Did you expect to find a couple of sinister characters peering at you by the light of a candle stuck in the neck of a bottle? Speaking of bottles…” The tall man glanced sideways as they all crossed the room toward the sideboard. When he spoke again, his voice was a little diffident, as if he were calling Weston’s attention to a point of local etiquette with which the new man could hardly be expected to be familiar. “I say, Weston. That gun you’re carrying, fella. I mean, how about parking it out in the hall, hunh? Just as a favor?”

Hesitating, Weston was aware that the bedroom door, to his right, had moved a little as if someone behind it had brushed it, changing position. Well, it was hardly likely they were going to shoot him here, he thought. He faced the tall man, deliberately turning his back to the slightly open door.

“I mean,” he said, “if you want it, how about taking it away from me?”

The challenge sounded brash and melodramatic in the pleasant surroundings. There was no check or break in the tall man’s movement as he arranged the glasses before him on the sideboard and reached for the martini pitcher. He did not even look up. But you could sense a certain tension.

“I can, you know,” he said mildly.

“I know you can,” Weston said. “But is it worth the trouble? You might even have to shoot me; and I’m no good to you dead.” He did not turn his head or change the sound of his voice. “Marilyn, you’re going to get an elbow…”

When a person stepped behind you at a time like this there were two good explanations for the act: they could be preparing to help disarm you, but they could also, unlikely as it might seem, be trying to shield you from the fire of a gun aimed at your back… The thought gave him a momentary pleasure, but he called himself a fool. There was no decision to be made, because the treatment was the same in either case.

The man in front of Weston inclined his head slightly, and the girl behind Weston moved away.

Louis smiled. “All right. If you feel so strongly about it, we’ll pass the gun.”

“Is that a bargain,” Weston demanded, “or do I order a rearview mirror to see what she’s up to now?

“It’s a bargain.”

Weston studied the long, pale, rather handsome face for a moment. Then he took Marilyn’s little automatic pistol from his pocket and laid it on the sideboard and grinned.

“The script was strictly horse-opera,” he admitted. “I wouldn’t know what to do with the gadget if I did have to use it.” He glanced at the girl standing by the fireplace now. “I just wanted to see which way the outlying counties would vote.”

She raised her head a little, startled.

He said, speaking to her directly, “Stay out from behind me. Stay where I can see you if you want to stay pretty.”

“There’s no need for threats, Weston,” Louis said reprovingly.

“No,” he agreed. “Give the lush her drink and let’s—”

“That’s enough!” The tall man stepped forward, annoyed. Marilyn’s face was quite pale. She did not move.

There was a certain pleasure to be had from knocking the props out from under all this fake gentility, whatever the reasons for doing it: whether he was punishing her for betraying him or shielding her from the consequences of trying to help him. He did not know which, and something inside him needed to keep hurting her.

“Well, that’s what she is, isn’t she?” he snapped. “Look at her—she’s been tanking up all afternoon. It’s a wonder she can still—”

“I said, enough!”

There was a brief silence. Then the tall man chuckled with sudden understanding.

“I see,” he murmured. “You really thought she’d back you up, didn’t you?”

“She backed me up, all right,” Weston said bitterly.

After dinner, the boy in the white jacket brought them coffee in the living room. Louis spoke casually over his shoulder, telling somebody to get himself something to eat, and a short, square man in a threadbare brown suit came out of the bedroom. While the door was open, Weston caught a glimpse of a machine resembling a dictaphone in the far corner of the room, presumably the receiving end of the microphones downstairs. He made a gesture in that direction as the door closed and the man in the brown suit went on into the kitchen.

“What’s the matter, don’t you trust her, either?” he asked sarcastically.

Louis frowned. “Oh, the microphones? They were installed for another purpose. A gentleman in whom we were interested kept a blonde friend in the apartment downstairs. Since the information we were trying to get was quite technical and the girl not very bright, her reports turned out to be utterly useless… No,” the tall man said, catching Weston’s look, “Elaine wasn’t here at the time, unfortunately. She is very clever about technical information. But we had to go to considerable expense to enable someone else to take down what the man said: hence the microphones.”

Weston glanced again at the girl in the expensive chiffon evening gown, stirring her coffee absently with a tiny spoon. He tried to imagine her tricking and wheedling a man into talking about something he would undoubtedly know should be kept secret; getting him drunk, perhaps, teasing him, offering herself and at the last moment withholding… Elaine is very clever about technical information! He found that he had shivered a little. “What happened to the blonde?”

“Oh, she is on another assignment now. We retained the apartments because they were conveniently located.”

Weston said, “When I called the F.B.I. this morning, they seemed to know all about this place. Doesn’t that kind of limit its usefulness?”

Louis chuckled. “You’d be surprised how many places the F.B.I. know about, and we know they know about, and they know we know they know, if you follow me. It’s a form of prestidigitation, fella. The hand is quicker than the eye, that kind of thing. Often we will run one kind of semi-illicit activity to distract their attention, while something entirely different and much more important is going on in the same place, unsuspected. And of course, very often they’ll pursue an obvious line of inquiry to camouflage a more dangerous investigation, as you have reason to know.”

“What do you mean?”

“Oh, I don’t say they weren’t mildly interested in questioning you yesterday, but mainly they used you as an excuse to look around the place without publicizing what they were really after.”

Weston said dryly, “Is that supposed to make me feel good about it?”

“How you feel, fella,” said Louis smiling, “is probably one of the least of J. Edgar Hoover’s many worries.”

“And what were they after?” Weston asked.

Louis glanced at him consideringly. “I don’t suppose

it’s ever occurred to you,” he said after a pause, “how ideal a small oil company could be for a man with, shall we say, certain outside interests. Such a company has contacts with the oil, steel, automotive, and aircraft industries, either as buyer or seller. And if the company is small enough, a man in almost any responsible job quite naturally has a knowledge of everything that’s going on. He is expected to help deal with all facets of the company’s business. You, yourself, as chemist, probably were in touch with most of it.”

Weston nodded.

The tall man went on, “You might even have arranged to intercept various communications, apparently from customers or suppliers, if you had wanted to. Mightn’t you? And then sent them on in the guise of routine correspondence? In code, of course, so that if a message went astray it would look, to the casual eye, like an ordinary business letter, or technical report, or advertisement…”

“It could have been done, all right,” Weston agreed calmly, while his mind grappled with the sudden question: Who?

Who, of the people with whom he had worked for a year and a half, had also carried a secret—better hidden than his own, which was known to both Doc and Jane Collis? Which of them, casually offering to run down for the mail for Janie, as they all did from time to time, had been concealing behind the friendly offers a desperate urgency, had been furtively slipping the betraying, treasonable messages out of the pack on his way back upstairs. Janie herself, or even Doc… He realized that he was taking for granted that the thing had been worked from the laboratory, perhaps because he, himself, had become involved. But the fact that the F.B.I. had used him as an excuse did not necessarily mean they believed the guilty person to be someone close to him; his record just made him a convenient whipping boy. The letters could have been addressed to the plant foreman as bills of lading, or to Mr. French. Any of the girls in the office had access to the mail desk. A man in almost any responsible job, Louis had said, but you did not have to take Louis’ word for it that it was a man. Anybody in the place could have done it, although for some it would have been easier than for others.

The Two-Shoot Gun

The Two-Shoot Gun Mad River

Mad River Texas Fever

Texas Fever Ambush at Blanco Canyon

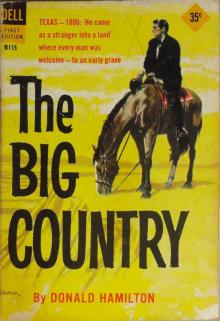

Ambush at Blanco Canyon The Big Country

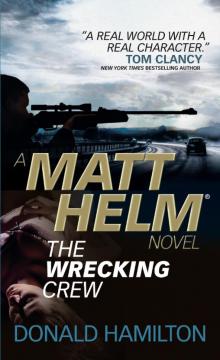

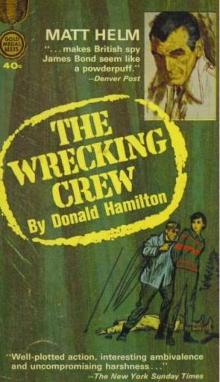

The Big Country The Wrecking Crew

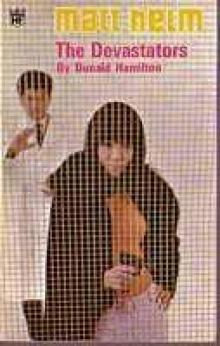

The Wrecking Crew The Devastators mh-9

The Devastators mh-9 The Wrecking Crew mh-2

The Wrecking Crew mh-2 The Shadowers mh-7

The Shadowers mh-7 The Ambushers mh-6

The Ambushers mh-6 The Betrayers

The Betrayers The Terrorizers

The Terrorizers The Poisoners

The Poisoners The Devastators

The Devastators The Silencers mh-5

The Silencers mh-5 The Interlopers mh-12

The Interlopers mh-12 The Shadowers

The Shadowers The Annihilators

The Annihilators The Vanishers

The Vanishers Night Walker

Night Walker The Revengers

The Revengers The Frighteners

The Frighteners The Infiltrators

The Infiltrators The Intriguers mh-14

The Intriguers mh-14 The Steel Mirror

The Steel Mirror The Menacers

The Menacers Assassins Have Starry Eyes

Assassins Have Starry Eyes Death of a Citizen

Death of a Citizen Matt Helm--The Interlopers

Matt Helm--The Interlopers The Removers mh-3

The Removers mh-3 The Demolishers

The Demolishers Murder Twice Told

Murder Twice Told The Poisoners mh-13

The Poisoners mh-13 The Ambushers

The Ambushers Death of a Citizen mh-1

Death of a Citizen mh-1 The Silencers

The Silencers The Removers

The Removers The Intimidators

The Intimidators The Damagers

The Damagers The Menacers mh-11

The Menacers mh-11 The Retaliators

The Retaliators Murderers' Row

Murderers' Row The Ravagers

The Ravagers The Ravagers mh-8

The Ravagers mh-8 The Threateners

The Threateners The Betrayers mh-10

The Betrayers mh-10