- Home

- Donald Hamilton

The Wrecking Crew Page 2

The Wrecking Crew Read online

Page 2

He frowned at me for a moment. “Vance is still with us, incidentally,” he said. “If you’ve forgotten what he looks like—we’ve all changed a bit since those days— you can identify him by the scar just above the elbow where the bone came out through the skin. Keep that in mind. He’ll be your direct contact with me, if for any reason you should find it inadvisable to use the regular channels of communication you’ve been told about.” He pursed his lips. “Of course, other departments have much greater facilities for transmitting messages than we have, and they give us wonderful cooperation, but you might just feel like sending something meant for my eyes alone. Or I might want to send something for yours. Vance will pass it on, either way. He’s operating on the continent, but the plane service is excellent, if you should need assistance.”

“Yes, sir,” I said.

He glanced at the training-course records again. “As for this stuff,” he said, “whether or not it’s precisely accurate doesn’t matter, since the first thing I want you to do, when you leave this room, is forget everything you’ve just been taught. If I’d thought this job required a man trained to razor-edge perfection, I wouldn’t have picked one well along in his thirties, a man who’s been outside the organization, wielding nothing more lethal than camera and typewriter, for fifteen years. Do you understand what I’m trying to tell you?”

“Not completely, sir,” I said. “You’ll have to spell it out for me.”

He said, “I had you put through the mill for your own sake. I couldn’t in good conscience send you out so rusty and out of condition you’d get yourself killed. Besides, we’ve developed some new techniques since your time, which I thought you’d like to know about. But in many ways you’d have been better prepared for the job at hand if you’d spent the past month in a hotel room with a bottle and a blonde. Now you’ll have to use restraint. Don’t betray yourself by showing off any of the pretty tricks you’ve just learned. If somebody wants to follow you, let them follow; you don’t even know they’re there. What’s more, you don’t care. If they want to search your belongings, don’t set any traps for them. If you should get involved in a fight-—God forbid—forget about weapons except in a clear and desperate emergency. And don’t give any unnecessary judo demonstrations, either. Just lead with your right and take your licking like a man. Do I make myself clear?”

“Well, I begin to see daylight through the mists, sir.”

He said, “I was sorry to hear that your wife has left you, but this project ought to take your mind off your marital troubles for a while.” He glanced at me sharply. “I suppose that’s why you suddenly changed your mind about coming back to work, after turning me down twice.”

“Yes, sir,” I said.

He frowned at me. “It’s been a long time, hasn’t it? I don’t mind saying that I’m glad to have you. You may be a trifle soft in the body, but you can’t possibly be as bad as the youngsters we get nowadays, who are practically all soft in the head… You’ll be taking considerable risk, of course,” he went on more briskly. “I feel that the risk will be lessened by a deliberate show of ineptness, but this means that you’ll be a sitting duck for anybody who really wants you out of the way. You’ll have to give the other fellow all the breaks. But it’s a foregone conclusion that they’re going to test you out carefully before they accept you as harmless, and you don’t want to scare them off. We’ve got a good cover for you, but one clever, professional move on your part will blow it instantly. You don’t know anything like that, except what you’ve seen in the movies. You’re just a hick free-lance photographer on his first assignment for a big New York magazine, aching to make good. That’s all you are. Don’t forget it for a minute. The job, and maybe even your life, may depend on it.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Your target,” Mac said, “is a man named Caselius. At least that’s the only name he uses that seems to be known. He undoubtedly has others. He’s apparently a pretty good man in his line, which is espionage. He’s bothering our earnest counter-intelligence people no end, so that they’ve finally overcome their humanitarian scruples and put in a request for us to take action. The fact that the man seems to be dangerous may have influenced them slightly. They’ve lost a number of agents who got too close to this mysterious fellow; and there was an incident last year involving a magazine writer, a chap named Harold Taylor, who published a popular article on Soviet espionage in general and Mister Caselius in particular. It was the first time, to our knowledge, that the name had appeared in print.

“Shortly thereafter Taylor and his wife were accidentally sprinkled with a full clip of submachine-gun bullets while stopped at a road block in the wrong part of Germany. A careless sentry and a mechanical malfunction was the official explanation. There seems to be little doubt among our people that Caselius was responsible. Apparently Taylor had learned too much, somehow. This is the angle you’re supposed to exploit.”

“Exploit how?” I asked. “It’s been a long time since I’ve used a ouija board, sir.”

Mac ignored my feeble attempt at witticism. “Taylor was killed instantly, according to the reports. His wife, however, was only wounded, and survived. She was returned to our side of the so-called curtain after considerable delay, for which medical reasons were given. There were many official apologies and expressions of regret, of course. She is now in Stockholm, Sweden, ostensibly trying to continue her late husband’s writing career on her own hook. She has turned out a magazine article on iron mining in northern Sweden that requires photographic illustrations. I have arranged for you to be the man assigned by the magazine in question to take the pictures.

“Our intelligence people over there seem to think there’s something fishy about the accident to her husband, about her long detention in the East German hospital, and even about her sudden decision to take up article writing. In any case, you are to use her as a starting point. Guilty or innocent, she may lead you, somehow, to Caselius. Or you may have to figure out another angle. How you do it is your business. When you’ve made your touch, report back to me.”

The word seemed to bring a slight chill into the office. The Russians prefer the word liquidate. The syndicate boys call it making a hit. But we’d always referred to it as a touch, for no reason anybody’d ever figured out.

“Yes, sir,” I said.

“Eric,” he said, using my code name, as was our practice.

“Sir?”

“A little of that sirring goes a long way, Eric. We’re not in the army now.”

“No, sir,” I said. It was an old running joke between us, dating back to the time I’d first come to the outfit as an overeager young second lieutenant, happy to be singled out for special duty, even though I didn’t know what it was or why I’d been chosen. “I’ll certainly remember that, sir,” I said with a straight face.

He gave me a glimpse of his rare, wintry smile. “Just a few more things before you go,” he said. “You haven’t had many dealings with these people. Just remember that they’re as tough as the Nazis ever were and maybe even a shade smarter; at least they don’t go around claiming to be supermen. Remember that you aren’t quite as young as you were when we used to send you over into occupied France. And, finally, remember that you could get by with certain things in wartime that won’t pass in time of peace. This is a friendly country you’ll be visiting. You not only have to find your man and make the touch, you have to make it look good. You can’t shoot it out with their police and run for the border, if you make a mistake.” He hesitated. “Eric.”

“Sir?”

“About your wife. Would it help if I were to speak with her?”

“I doubt it,” I said. “All you could do would be to tell her the truth about the kind of work we did during the war, and that’s just what she’s recently discovered for herself. She can’t make herself forget it. It got so she couldn’t stand to have me come near her.” I shrugged my shoulders. “Well, it was bound to happen. I just tried to kid myself I could

get away from it for good. I really had no business getting married and having a family. But thanks for the offer.”

He said, “If you get into trouble, we’ll do what we can unofficially, but officially we never heard of you. Good luck.”

All of this, some of it quite beside the point, went through my mind as I stood there holding the phone. The person behind me had made no real sound, but I knew quite well that I had company. I didn’t turn, but casually stretched out a foot, hooked a chair within reach, and sat down, as a woman’s voice came over the wire.

“Yes?”

“Mrs. Taylor?” I said.

“Yes, this is Mrs. Taylor.”

Well, it wasn’t the woman with the blue hair. This was a much deeper voice than the one I’d heard at the railroad station. I got an impression of a brusque and businesslike female who didn’t approve of wasting time with idle amenities. Perhaps I was prejudiced by my knowledge that Louise Taylor had been a journalist’s wife and had done some writing herself. On the whole, my experience with literary ladies hasn’t been encouraging.

“This is Matt Helm, Mrs. Taylor,” I said.

“Oh, yes, the photographer,” she said. “I’ve been expecting you. Where are you now?”

“Right in the hotel,” I said. “The train was late; I just got in. If you have some time to spare, Mrs. Taylor, I’d like to discuss the article with you before I fly north to do the pix.”

She hesitated, as if I’d said something surprising. Then she said, “Why don’t you come to my room, and well talk about it over a drink? But I must warn you, Mr. Helm, if you’re a bourbon man, you’ll have to bring your own. I’m hoarding my last bottle. They never heard of the stuff over here. I’ve got plenty of Scotch, though.”

“Scotch will do me fine, Mrs. Taylor,” I said. “I’ll be down as soon as I put on a clean shirt.”

I hung up. Then I turned from the instrument casually. It wasn’t the easiest thing in the world to do, and I was careful to move slowly enough, I hoped, not to startle my unknown roommate into precipitate action.

I could have saved myself the trouble. She was just standing there, empty-handed and harmless—if any pretty woman can be called harmless—with her expensive tweed suit and severe silk blouse and soft blue hair. Well, I’d told myself that if she really had some reason for wanting to talk with me, she’d turn up again.

3

We paced each other for a moment in silence, while I dropped my jaw and widened my eyes to register the emotions proper to finding myself—surprise, surprise— not alone. It gave me a chance to look her over more carefully than I had hitherto done.

The hair was really blue, I saw; it had not been an optical illusion, and it was not merely that vague rinse that grayhaired women often apply for reasons incomprehensible to the male of the species. This was, as I’d judged, prematurely white hair, very fine in texture, meticulously waved and set, and dyed a pale but definite shade of blue. When you got over the initial shock, it looked smart and striking as a frame for her young-looking face and violet-blue eyes. But I can’t say I really liked it.

It was an interesting effect, but I’m not partial to women who go in for interesting, artificial, calculated effects. They arouse in me the perverted desire to dump them into the nearest swimming pool, or get them sloppy drunk, or rape them—anything to learn if there’s a real woman under all the camouflage.

Having registered surprise, I let myself grin slowly. “Well, well!” I said. “This is real nice, ma’am! I think I’m going to like Stockholm. Is there one of you for every room, or are you just a special treat for visiting Americans?” Then I hardened my voice. “All right, sister, what’s the racket? You’ve been trailing me around ever since I set foot on shore, trying for a pickup. Now you listen carefully. It would be a bad mistake for you to rip that handsome blouse and threaten to start screaming, or have your husband charge in, or whatever similar stunt you have in mind.

“You see, ma’am, all us Americans aren’t millionaires, by a long shot. I don’t have enough money to make it worth your while, and if I did have I damn well wouldn’t pay off anyway. So why don’t you just run along and find yourself another sucker?”

She flushed; then she smiled faintly. “You did that very well, Mr. Helm,” she said, rather condescendingly. “Just the slightest tension in the shoulders when you realized I was standing here, almost imperceptible. The rest was very convincing. But then, they’d be bound to send a pretty good man after so many had failed, wouldn’t they?” I said, “Ma’am, you’ve sure got your signals crossed somewhere. I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

She said, “You can drop that phony drawl. I don’t think they really talk that way in Santa Fe, New Mexico. You’re Matthew Helm, age thirty-six, hair blond, eyes blue, height six-four, weight just under two hundred pounds. That’s what it says in the official description we received. But I don’t know where you hang two hundred pounds on that beanpole frame, my friend.”

She studied me for a moment. “As a matter of fact, you’re not really a very good man, are you? According to our information, you’re a retread, hauled out of retirement for this job because of your ideal qualifications with respect to background and languages. A trained agent with a genuine record of photo-journalism and a working knowledge of Swedish isn’t easy to come by. I suppose they had to do the best they could. Your department warned us that you might need a little nursemaiding, which is why I made a special trip to Gothenburg to keep an eye on you.” She frowned. “Just what is your department, anyway? The instructions we received were kind of vague on that point. I thought I knew most of the organizations we might have to work with.”

I didn’t answer her question. I was reflecting bitterly that Mac seemed to have done a fine job of giving me the reputation of a superannuated stumblebum. Perhaps it was necessary, but it certainly put me on the defensive here. The identity of my visitor was becoming fairly obvious, but it could still be a trick, and I said impatiently:

“Now, look, sister, be nice. Be smart. Go bother the guy in the next room for a while; maybe he likes mysterious female screwballs. I’ve got a date. You probably heard me make it. Will you get the hell out of here so I can wash up a little, or do I have to call the desk and have them send for a couple of husky characters in white jackets?”

She said, “The word is Aurora. Aurora Borealis. Your orders were to report to me the minute you reached Stockholm. Give me the countersign, please.”

That placed her. She was the Stockholm agent I was supposed to notify of my arrival. I said, “The Northern Lights burn brightly in the Land of the Midnight Sun.” I must have memorized half a thousand passwords and countersigns in my time, but I still feel like a damn fool when it comes time to give them. This specimen should tell you why—and at that, it isn’t half as silly as some I’ve had to deliver with a straight face.

“Very well,” said the woman before me, crisply. She gestured toward the telephone I had recently put down. “Now explain, if you please, why you chose to approach the subject before contacting me as instructed.”

She was pushing her authority very hard, and she didn’t really have much to push, but Mac had been explicit about what my attitude should be. “You’ll just have to grin and bear it,” he’d said. “Remember this is peace, God bless it. Be polite, be humble. That’s an order. Don’t get our dear, dedicated intelligence people all upset or they might wet their cute little lace panties.”

Mac didn’t ordinarily go in for scatological humor; it was a sign that he felt strongly about the kind of people we had to work with these days. He grimaced. “We’ve been asked to lend a hand, Eric, but if there’s a strong protest locally, we could also be asked to withdraw. There’s even a possibility, if you make yourself too unpopular, that some tender soul might get all wrought up and pull strings to embarrass us here in Washington. Every agent must be a public relations man these days.” He gave me his thin smile. “Do the best you can, and if you should haul off an

d clip one of them, please, please be careful not to kill him.”

So I held my temper in check, and refrained from pointing out that I was, technically, quite independent of her authority or anybody else’s except Mac’s. I didn’t even bother to tell her that her nursemaiding of me from Gothenburg to Stockholm—as she’d called it—and her presence in my room now, had probably left me with just about as much of my carefully constructed cover as a shelled Texas pecan. She wasn’t exactly inconspicuous, with that hair. Nobody watching me could have missed her. Her opposite number on the other team, here in Stockholm, would be bound to know who she was. Any hint of communication between us would make everybody I was to deal with very suspicious indeed.

I was supposed to have got in touch with her by telephone, when I judged it safe. By barging in like this, she’d knocked hell out of most of my plans. Well, it was done, and there was nothing to be gained by squawking about it. I’d just have to refigure my calculations to allow for it, if possible.

I said humbly, “I’m very sorry, Aurora—or should I say Miss Borealis. I didn’t mean to—”

She said, “My name is Sara. Sara Lundgren.”

“A Svenska girl, eh?”

She said stiffly, “My parents were of Swedish extraction, yes. Just like yours, according to the records. I happen to have been born in New York City, if it’s any business of yours.”

“None at all,” I said. “And I’m truly sorry if I’ve fouled things up in any way by calling the Taylor woman, but I’d sent her a radiogram from the boat saying I’d be here by three, and the train was late, so I thought I’d better get in touch with her before she got tired of waiting and left the hotel. I’d have checked with you tonight, Miss Lundgren, you may be sure.”

“Oh,” she said, slightly mollified. “Well, we might have had some important last-minute instructions for you; and I do think orders are made to be obeyed, don’t you? In any case I should think you’d want to hear what I know about the situation before you go barging into it like a bull buffalo. After all, this isn’t a ladies’ tea, you know. The man we’re after has already cost us three good agents dead, and one crippled and permanently insane from torture he wasn’t supposed to survive—not to mention the Taylor woman’s husband. We don’t really know what happened to him, except from her story, which may be the truth but probably isn’t. I know you were well-briefed before you left the States, but I should think you’d want the viewpoint of the agent on the spot as well.”

The Two-Shoot Gun

The Two-Shoot Gun Mad River

Mad River Texas Fever

Texas Fever Ambush at Blanco Canyon

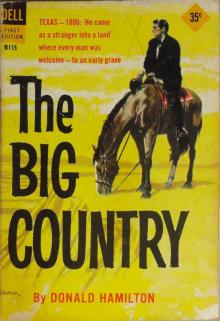

Ambush at Blanco Canyon The Big Country

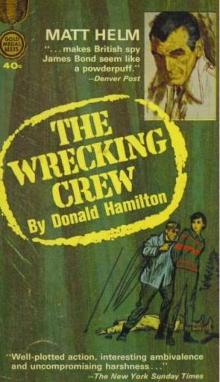

The Big Country The Wrecking Crew

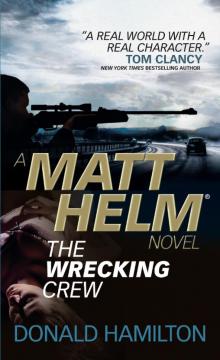

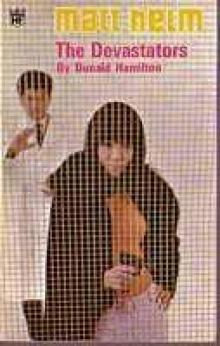

The Wrecking Crew The Devastators mh-9

The Devastators mh-9 The Wrecking Crew mh-2

The Wrecking Crew mh-2 The Shadowers mh-7

The Shadowers mh-7 The Ambushers mh-6

The Ambushers mh-6 The Betrayers

The Betrayers The Terrorizers

The Terrorizers The Poisoners

The Poisoners The Devastators

The Devastators The Silencers mh-5

The Silencers mh-5 The Interlopers mh-12

The Interlopers mh-12 The Shadowers

The Shadowers The Annihilators

The Annihilators The Vanishers

The Vanishers Night Walker

Night Walker The Revengers

The Revengers The Frighteners

The Frighteners The Infiltrators

The Infiltrators The Intriguers mh-14

The Intriguers mh-14 The Steel Mirror

The Steel Mirror The Menacers

The Menacers Assassins Have Starry Eyes

Assassins Have Starry Eyes Death of a Citizen

Death of a Citizen Matt Helm--The Interlopers

Matt Helm--The Interlopers The Removers mh-3

The Removers mh-3 The Demolishers

The Demolishers Murder Twice Told

Murder Twice Told The Poisoners mh-13

The Poisoners mh-13 The Ambushers

The Ambushers Death of a Citizen mh-1

Death of a Citizen mh-1 The Silencers

The Silencers The Removers

The Removers The Intimidators

The Intimidators The Damagers

The Damagers The Menacers mh-11

The Menacers mh-11 The Retaliators

The Retaliators Murderers' Row

Murderers' Row The Ravagers

The Ravagers The Ravagers mh-8

The Ravagers mh-8 The Threateners

The Threateners The Betrayers mh-10

The Betrayers mh-10