- Home

- Donald Hamilton

Death of a Citizen mh-1 Page 14

Death of a Citizen mh-1 Read online

Page 14

Figuring like this, confidently, I almost piled up in Glorieta Pass, not fifty miles from home. Coming up to a curve too fast, I suddenly discovered I had no more brakes than a roller skate. An ordinary car would have rolled and wound up at the bottom of the canyon, but this one kept right side up as I took the corner in a screaming slide, using the whole mad. It would have been a hell of a time to meet somebody coming the other way. After that, as long as I was in the hifis, I kept the transmission locked in second gear, used the compression judiciously to slow her down, and took it much easier. There wasn't that much of a hurry, anyway.

I made my entrance into town by way of a small dirt road instead of the main highway, just in case somebody might be watching for me. The first filling station I hit was closed, but it had a public phone booth outside. I stopped the car-the brakes had recovered enough for casual use-got out stiffly, and made my call to the number Mac had given me.

When somebody answered, I said, "This is the Dodge City, Santa Fe Express, coming in on Track Three."

"Who?" the guy said. Some people have no sense of humor. "Mr. Helm?"

"Yes, this is Helm."

"Your subject is still in his room at the DeCastro Hotel," the guy said. He had a clipped, business.like, Eastern voice. "He has company. Female."

"Who?"

"Nobody we're interested in. Just someone he picked up in the bar. What are your plans?"

"I'll be sitting in the lobby when he comes down," I said.

"Is that wise?"

"It remains to be seen," I said. "Don't call off the watchdogs. He might try to backdoor me."

"I'll be over there myself," the voice said. "There'll be a man standing phone watch at this number, however, in case you want to get in touch with us again. He'll be able to relay any messages to me."

"Very good," I said. "Thanks." I hung up, found another dime, and dialed again. There was only a little pause before Beth answered. If she'd been sleeping at all, it wasn't soundly. "Good morning," I said.

"Matt! Where are you?"

"I'm in Raton," I said. After all, there might be somebody on the line. "Ran into a little trouble in the mountains. The truck threw a connecting rod-I guess I was pushing too hard. But I've managed to wake up a guy who'll rent me a car, and I'll be on my way as soon as I hang up." That would explain the Plymouth, if anybody was watching when I drove up. It would also explain any delays, if I ran into trouble. I asked, "Any news? Any further instructions for me?"

"Not yet."

"Get any sleep?", "Not much," she said. "How could I?"

"That makes two of us," I said. "Okay. When somebody calls, tell her I may be just a little late, and explain why."

"Her?" Beth said.

"It'll be a her, this time," I said, hoping I was right.

CHAPTER 27

SHE was a Spauish-American girl, dark and willing-looking, but a little past the prettiest time of her life, which comes early among that race. She was wearing one of those small gray jackets made of nylon fur, over a yellow sweater and a tight gray skirt tricked out around the bottom with a lot of little pleats. Somehow, whenever one of those girls gets hold of a narrow skirt, which isn't often, it's always several inches too long; and the tartier the girl, strangely enough, the longer the skirt. You'd think it would be the other way around.

This one was pretty well hobbled. She came across the hotel lobby in her high heels and went out into the morning sunlight. Presently a man came in to buy a paper at the cigar counter. His crisp Eastern voice was familiar; I'd heard it over the phone quite recently. He walked on past me towards the coffee shop, a moderately tall character, well set up, in a gray suit-too young, handsome, and clean-cut for my taste, the epitome of a modern law-enforcement officer, no doubt, with good training in law or accounting as well as marksmanship and judo. He could have taken me with either hand, while lighting a cigarette with the other;

but he'd never get the chance; he was too nice a boy. I was going to have trouble with him. I could smell it.

He didn't look at me as he went past, but his head kind of bobbed in a nod, to tell me it was the right girl and things might start to happen, now that she was out of the way. It was about time. I'd been sitting there for an hour and a half.

He'd hardly gone out of sight when Loris appeared at the head of the short flight of stairs that led to the rear of the hotel, whatever might be there. He was yawning. He needed a shave, but with my beard,I was hardly in a position to criticize. I'd forgotten how big he was. He looked tremendously solid, standing there above me, and handsome in a bull-like way. The place was lousy with handsome young men. I felt old as the Sangre de Cristo peaks above the town, ugly as an adobe wall, and mean as a prairie rattlesnake. I'd driven four hundred miles in the truck since yesterday morning and five hundred miles in the Plymouth since last night, but it didn't matter. Weariness just served to anesthetize my conscience, if 1 had one, which wasn't likely. Mac had done his best to amputate it long ago. It was, he said, a handicap in our line of business.

Loris looked down and saw me. He wasn't very good. His eyes widened with recognition, and he glanced quickly towards the phone booths in the corner. Obviously his first impulse was to report this development and ask for advice.

I shook my head minutely, and made a slight gesture toward the street. Then I picked up the magazine I'd been pretending to read for an hour and a half, but I was aware that it took him several seconds to start moving again. He wasn't a lightning brain, by a long shot. I was counting on that.

He came down the steps and walked past me, hesitated, and went on out the front door. I got up casually and followed him. He was kind of shuffling his feet outside, moving off to the left slowly while waiting to see if I was coming. Now that I was here, he didn't want to lose me, even if he didn't quite know what to do with me. I wasn't supposed to be here this early.

He kept going, looking back to see that I was following, moving in the direction of the Santa Fe River, at this time of year a small trickle of water running over sand and rocks between high banks; in places the banks were reinforced by stone floodwalls. I've seen times when it came over the banks and walls and caused considerable local excitement. Along the river was a narrow green park with grass and trees and picnic tables; and the streets of the town went, over the stream on low, arched bridges, like giant culverts. Loris got to the park and headed upstream, cutting across the grass, past the picnic tables, obviously looking for a place where we could have a little privacy. He wanted enough privacy, I guessed, to be able to knock me around a bit, if necessary. It would be what came naturally into his mind.

I followed him, keeping my eyes on his broad back, hating him. I could afford to hate him now. There was no longer any need for calmness and clear thinking. I'd flushed him out of cover, I had him in the open, and I could think of Betsy, and of Beth waiting at home without sleep. I could even think, if I wanted to be petty, of a poke I'd once taken in the solar plexus, of a crack across the neck and a kick in the ribs. I could add up the balance sheet on Mr. Frank Loris and find, not much to my surprise, that there wasn't any really good reason for the guy to keep on living.

He picked the spot as well, as I could have picked it myself, in broad daylight with the town coming awake around us and all the law-abiding citizens hurrying off to their law-abiding jobs. He ducked down the bank, jumped from rock to rock down there, and vanished under a bridge. I slid down after him.

It was medium dark under the bridge. We had a wide street with sidewalks above us, and in the center the light had quite a ways to travel from the half-moonshaped openings at either end. The river made a little trickle of sound to my right as I walked towards him. He'd stopped to wait for me. As I came up, he was saying something. His attitude was impatient and bullying. I suppose he was asking what the hell I was doing there, and telling me what would happen to me or to Betsy if I was trying to pull something..

I didn't hear the words, maybe because of the sound of the river, maybe

because I simply wasn't listening. There was nothing he had to say that I had to hear. There were a couple of cars going past overhead. It was as good a time as any. I took out the gun and shot him five times in the chest.

CHAPTER 28

IT could have been done more neatly, but they were small bullets and he was a big man and I wanted to be sure. He looked very surprised-so surprised that he never moved at all in the time it took me to empty half a ten-shot clip. There was a gun of some kind under his armpit; I could see the bulge of it through his coat. He never reached for it. Me was a muscle man. They can seldom be trained to think in terms of weapons. He put down his head and charged, reaching for me with his big hands. I sidestepped and tripped him.

He went down and didn't get up again. The wheezy breath from his punctured lungs wasn't very pleasant to listen to. If he'd been a deer, I'd have put a quick one into his neck to cut it short, but you're not supposed to dispense that kind of mercy to human beings. Anyway, I didn't want the body to display any bullet-holes in the wrong places. Mac would want a reasonable story to give to the newspapers.

Loris collapsed and rolled over on his side. I reached down and took the revolver from under his armpit. It was a huge weapon, just the sort of hand cannon I'd expected him to lug around and then forget completely when he might have some use for it. It was wet with his blood. I carried it to the bridge opening, and stepped back quickly as I heard someone come running and sliding down the rocks towards me.

It was the Boy Scout in the gray suit. He charged in with drawn, short-barreled revolver in his hand. I suppose it took courage, and maybe that's the way you have to do it when you wear a badge and think a citizen's life may be at stake, but it seemed reckless and impractical to me.

"Drop it," I said from the shadows.

He started to turn, but checked himself. "Helm?"

"Drop it," I said. He'd be the kind to get excited and officious at the sight of a body full of bullet-holes.

''But-''

"Mister," I said softly, "drop it. I won't tell you again." I was beginning to shake just a little. Maybe it showed in my voice. The revolver dropped into the sand. I said, "Now step away from it." He did as he was told. I said, "Now turn around."

He turned and looked at me. "What the hell's got into you? I thought I heard shots-" A harsh, rattling sound made him look upstream. Apparently Loris was still alive. The guy in the gray suit looked that way, shocked. "Why," he said, "you crazy fool-"

I asked, "What were your instructions concerning me?"

"I was told to give you all the assistance-"

"Calling me names doesn't assist me much," I said. "You used us to finger the man!" he protested. "To point him out to you, so you could deliberately shoot him down!"

"What did you think I was going to do, kiss him on the cheek?"

He said, stiffly, "I realize how you must feel, Mr. Helm, with your little girl missing, but this kind of private justice-"

I said, "You're the only one talking about justice."

"Anyway, alive he might have led us to-"

"He'd have led us nowhere useful," I said. "He was dumb, but not that dumb. And he couldn't have been made to talk. Men like that have no imagination and no nervous system to work on. But he could, if something went wrong, have got to Betsy and harmed her. It's the only way he'd have led us to her, and we'd have had to wait until the last minute to make sure he was going to the right place. We might not have been able to stop him in time. Given a chance-and you'd have insisted on giving him a chance-he could have been a hard man to stop. I can do better with him out of the way." I glanced upstream. "I suppose you'll want to call an ambulance, since he's still breathing. Tell the doctor to be real careful. We wouldn't want him to live."

The young man in the gray suit looked distressed at my callousness. "Mr. Helm, you simply cannot take the law into your own hands."

I looked at him for a moment, and he shut up. "What's your name?" I asked.

"Bob Calhoun."

I said, "Mr. Calhoun, I want you to listen to me very closely. I'm trying to be a rational man of sound judgment. I'm trying very hard. But my little girl is in danger, and so help me God, if you get in my way with your damn fool scruples and legalisms, I'll swat you like a mosquito… Now this is what I want you to do. I want you to go back to that office of yours and keep that phone clear. I don't care who calls; get him off the line fast. If you've got to go to the john, have them bring a pot into the room for you. I'll be wanting you quick some time in the next couple of hours, and I don't want to have to stand around waiting for them to run you down with bloodhounds. Do I make myself clear, Mr. Calhoun?"

He said angrily, "Listen, Helm-"

I said, "You have your orders. You're supposed to assist me. Well, don't think about it, just do it. I can assure you that higher echelons will spray it all with perfume and tie it up with a pink ribbon, once it's over." I drew a long breath. "Keep that wire clear, Calhoun. And while you're waiting, get a crew of good men ready to move fast. Set up all the local cooperation you're going to need to wrap up a whole city block the minute I give you the address. You boys are supposed to be good at that stuff. It's out of my line; I'm leaving it to you. I'm counting on you to get my kid out safely, once I tell you where she is."

He said, "Very well. We'll do our best." His voice was stiff and reluctant, but pouter than it had been. He hesitated and said, "Mr. Helm?"

"Yes?"

"If you don't mind my asking," he said, "just what is your line?"

I glanced towards Loris, who was still breathing a little. You had to hand it to the guy, he was tough as a buffalo. But I didn't think he'd last much longer.

"Why," I said gently, "killing's my line, Mr. Calhoun." I turned and left the two of them there.

It seemed very odd to be coming home, like any businessman returning from a trip. I parked in the drive. The door burst open, and Beth came running towards me and stumbled into my arms. I held her kind of gingerly. If you feel a certain way about a woman, and your work involves, say, a garbage truck or a butcher shop, you like to clean up a bit before you put your hands on her. I couldn't help feeling I must stink of blood and gun powder, not to mention another woman.

"Any messages?" I asked after a little.

"Yes," she breathed, as if in answer to my thought. "A woman called. And… and there was something else…"

"What?"

"Something… something horrible…"

I drew a long breath. "Show me," I said.

She led me onto the porch. "She… told me over the phone to look out here. I don't know how long it had been here when she called, I didn't hear anybody… She said it was to… to change your mind, in case you were trying to be… clever…

It was a shoe box, tucked back in a corner behind one of our porch chairs, I suppose so the older kids wouldn't find and investigate it on their way to school. I pushed it out into the open with my foot, and looked at the box, and at my wife. Her face was white. I bent down and untied the string and opened the box. Our gray tomcat was inside, quite dead and rather messily disemboweled.

The funny thing was, it made me mad. It could have been so much worse; yet instead of feeling relieved, I was grieved and angry, remembering the fun the kids had had with the poor stupid beast, and all the mornings it had been at the kitchen door to greet me, meowing for its milk… I remembered also that this cat had once scared hell out of Tina by stowing away in the truck with her. She wasn't one to forget small injuries, if she could pay them back conveniently. Well, neither was I.

"Cover it up, please!" Beth said in a choked voice. "Poor Tiger! Matt, what kind of person would.

would do something like that?"

I put the lid back on the box and 'straightened up. I wanted to tell her: a person very much like me. It was a message from Tina to me. She was saying that the fun was over and from now on everything was strictly business and I could expect no concessions from her on the grounds of sentiment. Well, I had a me

ssage for her, too. And while I'm moderately fond of animals, and capable of feeling grief for a family pet, I can take an awful lot of dead cats if I have to.

"What are my instructions?" I asked.

Beth said, "Take… it out back. I'll get a shovel. It's Mrs. Garcia's day to clean the house. I'll tell you out there."

I nodded and picked up the box, carried it into the back yard, and set it down near the softest looking spot in the flowerbed at the side of the studio. It occurred to me that I was practically making a career of disposing of bodies, human and animal. Beth joined me. I took the shovel and started to dig.

She said, "At ten o'clock, or as soon afterwards as you get here, you're supposed to drive out Cerrillos Road. There's a motel just outside the city limits on the right-hand side, a kind of truck stop with a gas station and restaurant-you remember the one, with shabby little cabins in back, red and white. Tony's Place. You're to go to the cabin farthest from the road. But don't park there. First leave your car where everybody else does, by the restaurant. And if anybody follows you, or anything happens, Betsy-"

"All right, no need to spell it out," I said as she hesitated. I stuck the box into the hole' I'd made and covered it up. I looked at my watch. "Check my time," I said. "A quarter of ten."

"I have ten of ten," she said, "but I'm just a little fast. Mart-"

"What?"

"She called you Eric once, by mistake. Why? She sounded as if… as if she knew you quite well. At the Darrels' party you said you'd never seen her before."

"That's right," I said. "I did say that, but it wasn't the truth. Beth…"

I patted the dirt into place over Tiger's grave, and straightened up-leaning on the long-handled shoveland looked at her. Her light-brown hair was a little rumpled, as if she hadn't spent much time on it this morning, but it looked soft and bright in the sunshine. She was wearing a loose green sweater and a green plaid skirt, and she looked very young, like the college girl I'd married when I'd had no business marrying anyone-young, and tired, and scared, and pretty, and innocent.

The Two-Shoot Gun

The Two-Shoot Gun Mad River

Mad River Texas Fever

Texas Fever Ambush at Blanco Canyon

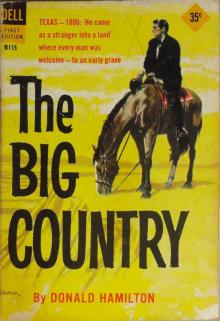

Ambush at Blanco Canyon The Big Country

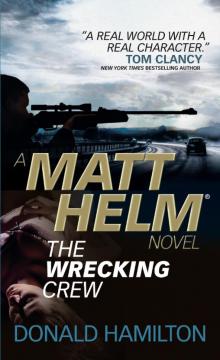

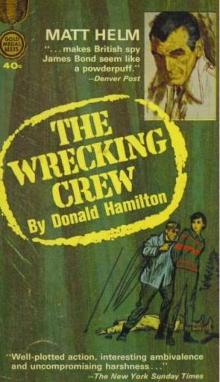

The Big Country The Wrecking Crew

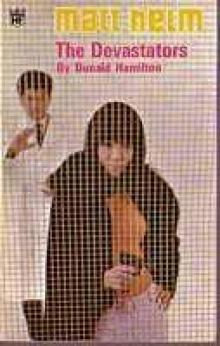

The Wrecking Crew The Devastators mh-9

The Devastators mh-9 The Wrecking Crew mh-2

The Wrecking Crew mh-2 The Shadowers mh-7

The Shadowers mh-7 The Ambushers mh-6

The Ambushers mh-6 The Betrayers

The Betrayers The Terrorizers

The Terrorizers The Poisoners

The Poisoners The Devastators

The Devastators The Silencers mh-5

The Silencers mh-5 The Interlopers mh-12

The Interlopers mh-12 The Shadowers

The Shadowers The Annihilators

The Annihilators The Vanishers

The Vanishers Night Walker

Night Walker The Revengers

The Revengers The Frighteners

The Frighteners The Infiltrators

The Infiltrators The Intriguers mh-14

The Intriguers mh-14 The Steel Mirror

The Steel Mirror The Menacers

The Menacers Assassins Have Starry Eyes

Assassins Have Starry Eyes Death of a Citizen

Death of a Citizen Matt Helm--The Interlopers

Matt Helm--The Interlopers The Removers mh-3

The Removers mh-3 The Demolishers

The Demolishers Murder Twice Told

Murder Twice Told The Poisoners mh-13

The Poisoners mh-13 The Ambushers

The Ambushers Death of a Citizen mh-1

Death of a Citizen mh-1 The Silencers

The Silencers The Removers

The Removers The Intimidators

The Intimidators The Damagers

The Damagers The Menacers mh-11

The Menacers mh-11 The Retaliators

The Retaliators Murderers' Row

Murderers' Row The Ravagers

The Ravagers The Ravagers mh-8

The Ravagers mh-8 The Threateners

The Threateners The Betrayers mh-10

The Betrayers mh-10