- Home

- Donald Hamilton

Texas Fever Page 13

Texas Fever Read online

Page 13

The boy would come here to claim her, openly, unarmed except for his silly great knife, and Keller would shoot him down. . . . Her brush-strokes faltered and stopped. Suddenly she buried her face in her hands and began to cry helplessly. It was a trap she’d led them both into, assuming a courage she did not possess. There was no escape.

CHAPTER 23

Awakening, Chuck McAuliffe was immediately aware that he was alone, but he wasn’t at first quite clear in his mind why this should be a cause for concern. After all, he’d awakened alone in his bed or blankets every other morning of his life.

Then the events of the night came back to him, and he opened his eyes and sat up quickly. The room was quite empty. There was no sign of his midnight visitor. He might have dreamed the whole incident; except that he knew he had not. It had happened, there was no doubt about that.

He got up and dressed quickly, wondering why she had slipped away. He also found himself wondering, in the cold light of morning, just what it would be like to be married. Well, that card was played. There was no picking it up now, even if he’d wanted to. It was just a matter of finding her and talking sense into her again, if necessary; and if anybody had any comments about his choice of a bride, they could damn well refrain from making them aloud. A McAuliffe paid his debts and kept his word.

He clapped his hat on his head and went down the stairs, aware again of the bruises and lacerations picked up in his fight with Will Reese. It seemed like a long time ago . . . if you could call it a fight, he reflected ruefully; it had been more of a massacre, the way he remembered it. Well, that was another debt that would be paid before long. At the foot of the stairs, he paused to regard the people in the lobby and the high sunshine in the square, visible through the door beyond. He must have slept like a bear holed up for the winter.

The lateness of the hour made him uneasy; and although he’d had some thought of taking a circumspect look around first, he turned and walked down the corridor directly to Room 11, and knocked on the door. Waiting, he reached back and felt the hilt of his knife: if Keller was inside, and wanted trouble, trouble was what he’d get

He heard a sound of movement and stepped back, but the man who opened the door was not Keller, or Bristow, or whatever he chose to call himself. It was Mr. Paine, the one they’d called the Preacher, in his rumpled black clothes, with bloodshot eyes. He opened the door only a crack, and peered out wanly.

“Who is it?” He frowned at Chuck. “Oh, it’s you again, friend. What do you want now?”

It did not seem wise to announce his mission, and Chuck said, “Why, you said for me to come back in the morning. I thought you might have reconsidered. . . ." Something about the man’s furtive look aroused his suspicion, and he asked, “What are you hiding in there? Is anything wrong?”

“Wrong?” The Preacher’s voice was smooth. “What would be wrong, friend? As for reconsidering, I believe my . . . my associate gave you your answer last night, and I see no reason to misdoubt his judgment.”

“Where is Keller? Maybe I could persuade him—” Paine said, “Mr. Bristow sent a message that he’d meet us at the auction down on Spring Creek. I’d say he expects to buy some cattle there; and it seems highly unlikely that you can persuade him to give you money to defeat his purpose. Now, if you’ll excuse me . . .” He started to withdraw, never having opened the door more than six inches. Chuck moved abruptly, putting his boot into the crack as it started to close.

“Just a minute, friend!”

There was a brief scuffle. The older man tried to kick away the obstructing foot. The Bowie knife gleamed in the opening, and Paine recoiled, letting the door swing free. Chuck pushed it wide, and stepped inside cautiously, knife ready, watching the man before him but ready for attack from either flank. With his elbow, he swung the door fully back against the wall, assuring himself that no one was hiding behind it. He stepped clear of it. There seemed to be no one in the room to explain the Preacher’s wary attitude. Then Chuck became aware of the still figure in the bed.

The Preacher spoke. “I suggest that you close the door, my boy. . . . That’s better.”

Chuck stared at the motionless shape of the girl. She was lying there with her hair outspread on the pillow and her lips slightly parted. Her eyes were wide open, looking at nothing.

Chuck whispered, “What. . . who . . . ?”

“Turn the key in the lock . . . so.” The older man’s voice was soft. “Now I think you can sheath that menacing weapon, young man. I did not kill her, I assure you.” After a moment, watching him, the Preacher murmured: “I see. You came here to find her, is that it? That would seem to indicate that she visited you last night, before. . . . What happened? Was your virtue unassailable, friend? Did she find in you no shining knight to come to her rescue? Is that why she . . . ?”

Chuck turned his head. “Be quiet, old man.”

“Yes,” Paine said. “Yes, to be sure.”

Chuck stared at him for a moment without seeing him clearly. Then Chuck turned, shoving the big knife back into its sheath, and walked slowly up to the bed. He hesitated, and reached out and closed the staring eyes, as he’d seen it done more than once along the trail. He noted that there was a small bottle of medicinal appearance on the coverlet near her hand.

“Laudanum,” the Preacher said, behind him. “It’s very popular for the purpose. There would have been no pain.” Chuck said dully, “I asked her to marry me. She was going to Texas to wait for me.”

“I see.” The older man’s voice was gentler. “My apologies, then. To both of you.”

Chuck swung to face him. “What do you mean?” Paine did not speak, and Chuck demanded: “What are you doing in here?”

The Preacher shrugged. “After the messenger from . . . er . . . Mr. Bristow awakened me, I found myself requiring a little stimulant. There was none in my room so I came in here. She was lying as you see her. Then you knocked on the door. . . . I suggest you take your leave now. I will do what’s necessary. I was . . . quite fond of her, myself. In a fatherly way, of course.”

Chuck said quickly, “I’ve no intention of leaving her—”

“Of course you’re leaving,” the older man said. “You can do nothing for her now, nothing that I cannot do as well. What can you accomplish by staying, except make trouble for everybody?”

“But—”

“You young fool,” the Preacher said, “if she did it for anyone, she did it for you. Think about that. Will you spoil her last fine gesture for some notion of pride? Now get out of here . . . Oh, pass me that bottle on your way. Thank you.”

Chuck paused at the door. “What will you do?”

“Why,” Paine said dryly, “I’ll discover her, of course, and give the alarm, in a state of shock and distress. As soon as I’ve built up my strength to a sufficient degree.” He shook the bottle in his hand, and measured the level of the liquid with his eye. “First I will contemplate the fact that small oblivion can be found in large bottles, and large oblivion in small ones. There must be a philosophical truth involved, somewhere. Good day, sir. . . ."

CHAPTER 24

Walking along the square, Chuck was barely aware of the warmth of the sun on his head and shoulders. If she did it for anyone, Paine had said, she did it for you . . . . He remembered, with shame, his rueful thoughts about marriage upon awakening. Perhaps she had known he would feel like this in the morning. Perhaps she had killed herself, rather than hold him to his promise. In any case, he felt like a coward for having left her with no one but an old drunk to look after her.

Thinking like this, he was only vaguely aware of an open buggy driving up beside him.

“Mr. McAuliffe.”

He stopped and turned. Jean Kincaid was looking down at him from the buggy seat. She was wearing the same calico dress he’d seen before, and her fair hair was softly arranged under her neat bonnet.

“Is . . . something amiss, Mr. McAuliffe? You look so——”

“No,” he said curtly

, “nothing’s amiss, ma’am.”

“And if it were,” she said wryly, “it would be none of my business, would it?” After a moment, she went on: “I thought you’d be down at Spring Creek for the auction. Dad rode down early.”

He’d taken off his hat politely enough, but he couldn’t manage to put any politeness into his voice. He said, “I think the coyotes can fight over the carcass without me watching.”

She smiled at this. “Dad being one of the coyotes, Mr. McAuliffe? You don’t like us very much, do you?” He said, avoiding a direct answer, “I’ll be leaving town as soon as I can, ma’am. I’m just waiting around to get our guns back-—assuming nobody figures out a nice legal way to separate us from those, too. I reckon there’s folks around here who’d just love to send us back through Indian Territory unarmed; and it would surely bring happiness into the lives of some of those Cherokee braves we scared off on the way up.”

She was still smiling. “You certainly do have a high opinion of us! But you shouldn’t be in too much of a hurry to ride off. You’ll have some money coming to you from the sale of the cattle.”

Something about her pretty air of tolerance was more than he could stomach. In her demure dress, holding the reins firmly in her small gloved hands, she seemed to represent everything he hated about this northern country—also, the mere fact that she was alive seemed to be a direct insult, under the circumstances. She was alive, well fed, neatly dressed, and smugly proud of herself for all the advantages she had that were none of her doing. She’d never known what it was to be part of a defeated nation; she’d never known misery and shame; the thought of taking her own life, under any circumstances, would never have crossed her mind. . . .

He knew that he should keep quiet; but suddenly he had to tell someone exactly what he thought and felt. At least he could wipe that infuriating look of smiling forbearance from her face.

He shook his head. “Money?” he said, “No, ma’am, I’m not really counting on any money.”

“What do you mean?” she asked quickly.

“Why,” he said deliberately, “I figure it’s already been arranged for the herd to go for the exact amount of the fine and costs. Your dad warned me not to expect much, and the fellow at the bank was kind enough to tell me nobody around here has much interest in Texas cattle. That seems to leave it up to these here visiting cattlebuyers Paine and Bristow—if you want to call them that—and I don’t reckon anybody’s going to embarrass a fine, upstanding Yankee citizen like Mr. Bristow by making him pay any more than just what’s necessary to make the transaction look all legal and proper.”

Her smile had faded. She said, shocked: “You don’t really believe—” She checked herself. “I can understand your resentment, but you’re being terribly prejudiced and unfair!”

“Unfair!” he said explosively. “What’s fair about us driving a herd of cattle eight hundred miles, at the cost of three lives from our own crew not to mention a few other deaths along the way—there was a little hard work and suffering involved, too, ma’am—only to have them taken away from us by a bunch of fine sanctimonious gentlemen who never slept on the ground or saw a river in flood!”

She said, “Mr. McAuliffe—”

He went on hotly: “You want me to ride down there and watch them throwing dice to decide who’s going to get my cattle for how much? No, thank you, ma’am! I’m staying right here in town and being a real good boy. That way, maybe I’ll get out of this nest of Yankee thieves with what’s left of my shirt. If I went down there, I might make the mistake of expressing my true feelings, and get myself thrown in jail for life!”

He had reached her at last. She started to speak angrily, stopped, and jerked her head sharply, indicating the seat beside her. “Come here, Mr. McAuliffe!” she snapped. “Come up here, where I can talk to you properly!”

“Thank you, ma’am, but—”

She said tightly, “You get up on this seat, or I’ll take the whip to you!” She reached over to snatch the implement from its socket.

Her anger pleased him. At least he’d managed to penetrate her armor of sweet female hypocrisy. He laughed scornfully and said, “Why, ma’am, did your gentleman friend, the deputy, send you here to finish the job he started yesterday? With a buggy whip?”

She stared at him for a moment, speechless; then she made an odd little sound in her throat, and let the whip drop back into place. She looked almost as if she were about to cry.

“I . . . I’m sorry,” she said almost inaudibly. “I don’t know what. . . got into me! You’re such a wrong-headed and irritating person. I . . . I lost my temper. Please. Come up here so we can talk. You can’t really believe all those things you said. . . . We can’t keep shouting at each other like this right here in the middle of town, there’ll be no end to the scandal. . . . Please?”

He hesitated, but she’d made her apology, and he could do no less than comply with her request, without seeming stubborn and ungracious.

“Very well, ma’am,” he said, and climbed in beside her. She shook the reins and spoke to the old bay gelding between the shafts. Neither of them said anything for several minutes after the rig was in motion. Then she spoke without looking at him.

“I suppose I’m responsible for . . . for your trouble yesterday, Mr. McAuliffe. I shouldn’t have . . . I didn’t mean to repeat what you . . . But Will knew I’d talked to you, and when I let slip . . . He was terribly angry.” Chuck said dryly, “Yes’m, I noticed that.”

“Did he hurt you very much?”

Chuck moved his shoulders. “I reckon I’ve taken worse lickings. Your dad stopped it before he got a chance to use his boots.”

She winced. “If it’s any satisfaction to you, I’m no longer engaged to marry Will Reese.”

He looked at her quickly, startled. “I’m sorry, Miss Kincaid. I never intended—”

“I’m sure you didn’t.” Her voice was tart. “You just go around making all kinds of reckless accusations, and it never occurs to you that . . . that someone may be . . . hurt.” She bit her lip. “I’d have believed Will,” she said quietly. “I’d have believed anything he told me. I’d have believed in him if he hadn’t told me anything, if he’d just expected me to trust him without words. But when he got absolutely furious and . . . and violent and insulting, when he marched out of the house like that, then I realized that what you’d said was . . . was probably true.” She glanced at Chuck. “I hope you’re pleased!” He said uncomfortably: “I’m sorry, ma’am, I—”

“You’ve already said that. I don’t believe it! I think the only person you’re sorry for is yourself. The whole world is against you, isn’t it, Mr. McAuliffe? Everybody’s taking unfair advantage of you. . . . Well, let me ask you just one question: who started it? I can under stand how you feel about losing your cattle, but why didn’t you think of that before you sent them charging at a duly constituted posse enforcing the law of the land—”

“The law of the land!” he said, stung into anger again. “This quarantine, ma’am? Why, I’ll bet half the folks who put that law through your state legislature didn’t give a d—excuse me, didn’t care a hoot about Spanish fever or protecting the poor farmers. They just saw a lot of Texas cattle coming up the trail and figured out a way to block them from market so they could get their hands on them cheap!”

She stared at him, aghast. “Why, you’re quite mad! Oh, maybe here and there a few people have taken advantage of the quarantine for their own profit, but—” Abruptly she reached for the whip at her side. “No, sit still, I’m not going to hit you, Mr. McAuliffe!” she snapped, flicking the aged horse lightly across the flank. “I’m just going to show you something. You claim to be a cattleman, maybe you’ll understand. Not that I really expect you to understand anything that doesn’t affect your feelings or your pocketbook!”

CHAPTER 25

It was a large, well-kept farm some miles from town, but much of the stock in the fenced pasture, lean and poor-looking, didn’t m

atch up with the prosperous appearance of the place. Jean Kincaid drove right up to the house. A plump little man with a red, round face and silky white hair came out to greet them. His welcoming smile became less warm as he recognized the girl’s companion.

“Good morning, Uncle Wayne,” Jean said. Her expression was polite and innocent as she turned to Chuck. “Mr. McAuliffe, I believe you’ve met my uncle, Judge Thomson.”

Chuck said grimly, “Yes’m, I made the judge’s acquaintance in court yesterday morning.”

The judge regarded Chuck without favor, and spoke to his niece: “Jeannie, girl, does your dad know you’re gallivanting around the countryside with—”

The girl laughed. “Oh, I’m perfectly safe with Mr. McAuliffe. He hasn’t got his big revolver back yet. . . . Uncle Wayne, do you mind if I show him around the place? Mr. McAuliffe thinks our concern over Texas fever is greatly exaggerated. He thinks our quarantine is just a sly Yankee plot to rob honest Texas citizens of their cattle. Oh, he admits we may have lost a few head here and there—”

“A few head!” The judge’s voice was harsh. “Half my purebred herd is dead, thanks to that one bunch of scrawny longhorns that came through here! And those that have recovered . . . well, look at them!” He waved his hand toward the pasture. “And it’s not over yet; new ones are still coming down with the fever. I’ve got the ailing stock penned up back of the barn. . . . Show the young man around, by all means! Just be careful of your pretty dress, it’s kind of dusty and dirty back there. A Yankee trick, indeed!”

He marched back into the house, shaking his head. Jean Kincaid glanced at Chuck, but didn’t speak. She guided the buggy around the building and through the ruts and dust of the farmyard. They didn’t get out; it wasn’t necessary. They sat there a while in silence; then the girl lifted the reins and spoke to the old horse and they drove away.

“Well, Mr. McAuliffe?” she murmured at last. He retained in his mind a dismal picture of handsome cattle of some eastern breed standing glassy-eyed and staring, of cattle with arched backs and sagging heads staggering from weakness, of cattle tossing their heads in a kind of delirious frenzy. . . .

The Two-Shoot Gun

The Two-Shoot Gun Mad River

Mad River Texas Fever

Texas Fever Ambush at Blanco Canyon

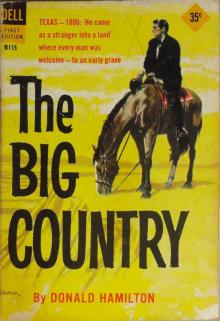

Ambush at Blanco Canyon The Big Country

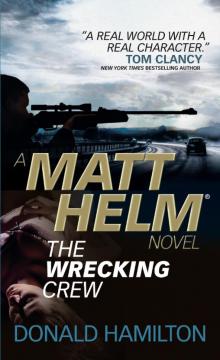

The Big Country The Wrecking Crew

The Wrecking Crew The Devastators mh-9

The Devastators mh-9 The Wrecking Crew mh-2

The Wrecking Crew mh-2 The Shadowers mh-7

The Shadowers mh-7 The Ambushers mh-6

The Ambushers mh-6 The Betrayers

The Betrayers The Terrorizers

The Terrorizers The Poisoners

The Poisoners The Devastators

The Devastators The Silencers mh-5

The Silencers mh-5 The Interlopers mh-12

The Interlopers mh-12 The Shadowers

The Shadowers The Annihilators

The Annihilators The Vanishers

The Vanishers Night Walker

Night Walker The Revengers

The Revengers The Frighteners

The Frighteners The Infiltrators

The Infiltrators The Intriguers mh-14

The Intriguers mh-14 The Steel Mirror

The Steel Mirror The Menacers

The Menacers Assassins Have Starry Eyes

Assassins Have Starry Eyes Death of a Citizen

Death of a Citizen Matt Helm--The Interlopers

Matt Helm--The Interlopers The Removers mh-3

The Removers mh-3 The Demolishers

The Demolishers Murder Twice Told

Murder Twice Told The Poisoners mh-13

The Poisoners mh-13 The Ambushers

The Ambushers Death of a Citizen mh-1

Death of a Citizen mh-1 The Silencers

The Silencers The Removers

The Removers The Intimidators

The Intimidators The Damagers

The Damagers The Menacers mh-11

The Menacers mh-11 The Retaliators

The Retaliators Murderers' Row

Murderers' Row The Ravagers

The Ravagers The Ravagers mh-8

The Ravagers mh-8 The Threateners

The Threateners The Betrayers mh-10

The Betrayers mh-10