- Home

- Donald Hamilton

The Wrecking Crew Page 13

The Wrecking Crew Read online

Page 13

“What do you mean?” I asked.

She didn’t look at me. “Skip it,” she said. “It was just a friendly warning. I just mean she’s a screwball, that’s what I mean. What were you two talking about at dinner, anyway, that was so fascinating?”

I said, “Well, if you must know, we were comparing the killing power of the American .30-06 cartridge, as applied to big game, with that of the European 8mm. She’s a strong eight-millimeter fan, you’ll be interested to hear.”

“Oh, for God’s sake,” Lou said. “Well, I told you she was a screwball.”

Then the taxi was pulling up at the hotel. I paid—I was getting quite handy with the local currency—and followed Lou inside. We climbed the stairs in silence and stopped in front of her door.

She hesitated, and turned to look at me. “Well, I guess that’s it,” she said. “It’s been quite an experience, anyway you look at it, hasn’t it?” After a moment, she said, “We really ought to have a farewell drink on it, don’t you think? I’ve still got some bourbon left. Come on in and help me polish it off.”

It wasn’t very subtle. Behind me was the door to my room, and behind that door, on the dresser top, were the films—if they were still there—the films I’d threatened to send off to America at the crack of dawn. I’d figured that time limit would draw some action, but I won’t say I’d anticipated it would take this form.

“All right,” I said. “I’ll come in, but just for a minute, if you don’t mind. It’s been a long day.”

It had been a long day, and it wasn’t over yet.

21

Closing the door behind me, I had the funny tight feeling you get when you know what’s coming, you just don’t know what she’s going to insist upon in the way of suitable, civilized preliminaries. There would be preliminaries, I was sure of that. Tonight it wouldn’t be the quick, casual, what-the-hell-we’re-both-adults approach she’d used before. That wouldn’t take up enough time.

Tonight she had to keep me busy for a while, out of that room across the hall, until somebody passed her the all-clear signal somehow. I wondered how they were going to manage that. The wrong-number trick wouldn’t work here, since there were no room phones in this arctic hotel. I watched her carry her coat to the closet and hang it up. She emerged with a bottle that had a homelike American look, and gave me a quick smile.

“I’ll be with you in a minute.”

“No rush,” I said.

She started to say something else, changed her mind, and went behind the curtain of the rudimentary bathroom in the corner for glasses and water. Waiting for her to emerge, I looked around the room. It was pretty much like mine. Being on the opposite side of the building, it didn’t have a window overlooking a vista of lake and trees—as a matter of fact, it faced the railroad station—but at night with the shade pulled down the view didn’t matter. Like any hotel room, it had a couple of beds for its primary pieces of furniture. These were large, old-fashioned iron bedsteads with brass knobs—wonderful old beds, really; I hadn’t seen any like them in actual use since I was a boy in Minnesota, although I’d seen plenty gathering dust in junk shops and antique stores.

There was also a comfortable upholstered chair, a hard wooden one painted white, an old white-painted dresser, a couple of small tables, and a rag rug on the floor. Although rather short of facilities considered essential elsewhere, it had a pretty nice atmosphere for a hotel room; certainly it was much more pleasant and spacious than the efficient, soulless little cubicles you get for twice the price in more modern hostelries. But as I say, in just about any hotel room, you can’t get away from the damn beds. I decided I’d be perverse and make the stalling she had to do as tough as possible. I walked over and sat down on the nearest bed, making the old springs creak plaintively.

She was in the bathroom for quite a while. Then she came out with a glass in each hand, looking slender and smart and attractive in her narrow, long-sleeved, lownecked black dress. It occurred to me that I could get very fond of this girl, if I let myself. You can’t work with someone for a week without coming to some conclusions about her, no matter how hard you try to avoid it. There was a moment, watching her approach, when I wanted very badly to break up this crummy business with a little injudicious honesty.

All I had to do was indicate in some way that I hadn’t the slightest intention of entering my own room until my presence there would embarrass nobody; that they were welcome as could be to the films on my dresser; and that there was no need whatever for her to buy them with her body. Of course, she’d have become suspicious instantly. Being as bright as the next person, or maybe a little brighter, she’d have wanted to know why I took such a casual attitude toward those all-important pix I hoped to trade for the information I needed...

Nevertheless, I was tempted. I couldn’t help thinking she was fundamentally a nice kid. I didn’t know how she’d got mixed up in this mess, and I didn’t care. If we could just get together and talk it out, instead of playing dirty games with liquor and sex, maybe we’d find that it was all a terrible misunderstanding… I was getting soft. I admit it. I was just about to break down and say something naive like: Lou, honey, let’s put our cards on the table before we do something lousy we’ll both regret. Then I saw that she had no stockings on.

She stopped before me and smiled down at me as I sat there on the big bed. “No ice, as usual,” she said. “I swear to God, the next time I come across a real highball with ice cubes, I’m going to take the lovely things out and suck them like candy, with tears in my eyes.”

I took the drink, and glanced again at her straight white legs, innocent of nylons. She’d been wearing them earlier, of course. I’d helped zip her up the back, remember; I’d patted her fanny in a friendly way. She’d been fully dressed then, completely enveloped in the ridiculous, delicate complex of nylon and elastic that holds the twentieth-century lady together. Well, I suppose it beats nineteenth-century whalebone, at that. But she wasn’t wearing it now. That was what she’d been doing behind the curtain: shedding. Now there was just Lou, naked under her party dress, with her bare feet stuck into her slim-heeled party pumps, as on one carefree, lighthearted morning a week or so ago.

It was like a kick in the teeth. She’d remembered, and carefully filed for reference, the fact that I’d once found her irresistible dressed—or undressed—a certain way. It was the one thing that had happened between us that had been wholly spontaneous and natural. Now she was deliberately using it against me.

I made myself whistle softly. I said dryly, “This is the place for the line that goes: my girdle was killing me.”

She had the grace to blush. Then she laughed, set her glass aside, and smoothed the clinging black jersey down her body, watching the effect with interest.

“I’m not very subtle, am I?” she murmured. “But then, what could I have worn, of the few things I have with me, that would have been subtle enough? I didn’t pack for a honeymoon, you know. Should I go back and change into my nice warm flannel pajamas?”

I didn’t say anything. She glanced at me sharply. Something changed in her face. After a moment, she seated herself beside me on the bed, picked up her glass, and drank deeply.

“I’m sorry, Matt.” Her voice was stiff. “I didn’t mean to... I wasn’t trying to seduce you, damn you. I didn’t think you needed it, to be perfectly honest.”

I didn’t say anything. It was her party.

She drew a long breath and drank again. “I misunderstood... We probably won’t be seeing each other after tomorrow, unless we happen to meet in Stockholm later. When you came in here, I thought you had a sentimental good-bye in mind, if you know what I mean. I guess I’ve made it pretty plain I had no objections.” She laughed ruefully. “There’s nothing more ridiculous, is there, than a woman who gets all ready to yield up her virtue, only to find she’s got no takers. Sex, anybody?” She laughed again, drained her glass, and rose. “How about another drink before you go? I need a little more to drown

my humiliation.”

I made a show of hesitating. Then I said, “Well, all right, just one more,” and emptied my glass and handed it up to her. I watched her cross the room with a slight unsteadiness that wasn’t necessarily faked; we’d both had quite a bit over the course of the evening. I felt kind of mean, just sitting there like a lump and making her carry the show all by herself. But when she returned, I saw that she’d studied her appearance carefully in the mirror and decided that, for the proper inebriated, uninhibited, delicious look, she’d better muss her hair a little and pull her dress slightly askew, just enough to tease me with a bit of shoulder and a bit of breast. I didn’t have to worry about her. She was a trouper.

“Tell me,” she said, dropping down beside me carelessly, “tell me about that woman.”

I rescued my glass from her hand before she could drench us both, as part of the act. “What woman?”

“The one who said she wouldn’t tell. You said to remind you. What wouldn’t she tell, and what did you do?”

“It’s hardly good bedroom conversation.”

Lou laughed softly, sitting close to me. “With you feeling so virtuous, what is?”

I said, “She wouldn’t tell me where she was holding my youngest child, Betsy, aged two.”

Lou glanced at me, startled, forgetting how drunk she was supposed to be. “Why did she have your little girl, Matt?” I didn’t answer at once, and she said, “This woman… this woman, did you know her before?”

“During the war,” I said. “We did a job together, never mind what.”

“Was she young and beautiful? Did you love her?”

“She was young and beautiful. I spent a week’s leave in London with her afterwards. I never saw her again until last year. You may know that some of the people who fought the war our way changed sides later, looking for the excitement they’d got used to—not to mention the crude subject of money. Nobody ever got rich, at least not legitimately, working under cover for Uncle Sam. It turned out she was one of those who changed sides. She needed some help with a job she was on for the other team. She had Betsy kidnaped to make me cooperate.”

“But you didn’t cooperate? Not even with your little girl’s life at stake?”

“Don’t give me credit for too much patriotism,” I said. “You just never get anywhere letting yourself be blackmailed, that’s all. To get Betsy back on her terms, I’d have had to kill a man for her; and even then I’d have had no assurance that she’d play it straight.”

Lou said, “So you tried to force the information from her. And she said she wouldn’t tell.”

“She said that,” I said. “But she was wrong.”

There was a little silence. Outside the hotel, the town was quiet. It wasn’t much of a town for traffic, particularly at night.

“I see,” Lou murmured. “And you got your child home safely?”

“The forces of law and order were very efficient, once they knew what address to be efficient at.”

“And the woman?” She waited for my answer. I didn’t say anything. Lou shivered slightly. “She died?”

“She died,” I said evenly. “And my wife came walking into the place right afterward, although I’d warned her that the less she knew the better she’d like it.” I grimaced. “It was a traumatic experience for her, I guess.”

“I should think so!”

I glanced at Lou irritably. “Traumatic, shaumatic! It was her child, too, wasn’t it? Did she want Betsy back or didn’t she? It was the only way of doing it. But the way Beth started pussy-footing around me afterward, you’d think I slipped out three evenings a week to carve up women for kicks.”

There was another silence. Lou drank from her glass, holding it with both hands and staring down into it. It was empty again. So was mine, somehow. Her weight was against me now, as we sat there on the big bed. She’d kicked her shoes off for comfort, and her bare feet, on the rag rug, looked more naked and immodest than her halfexposed breast. I hated her. I hated her because, despising the whole obvious business, I still couldn’t keep myself from wanting her badly, just as she’d planned from the start. It had been very neat, the way she’d brought up the subject, laughed at herself, and dismissed it. She’d put a nice reverse twist on the old seduction scene, but the plot and characters remained the same. Well, I’d played coy long enough.

I said, deliberately, “I suppose, like my wife, you couldn’t bear to have me touch you now, after hearing that story.”

She hesitated. Then she reached out quickly and took my hand and put it to her breast. It was a beautiful and touching gesture, something to bring tears to your eyes, except for that brief hesitation, that moment of calculation, that spoiled it completely.

I said, “You sweet goddamn little phony!” and pulled her to me hard.

I kissed her, brutally, until she gasped and turned her face away. Then the full charge of anger hit me, and I wanted to hurt her worse, to strike her—and I couldn’t do it. I was really pretty drunk, I guess, but something kept whispering: go easy, go easy, watch out, you know too many ways of killing people to horse around like this.

I couldn’t get away from that nagging whisper, but I could drag the dress from her shoulder roughly, remembering how concerned she’d always been about the precious garment. I could kiss her contemptuously on the neck and shoulder and bare arm and breast, forcing the cloth downward, feeling it stretch to its limits of elasticity and beyond. She caught at my wrist in protest as sleeve and bodice tore. To hell with her. I could play as dirty as anybody. She was just a lousy little amateur; she shouldn’t have tried it on an expert.

My fingers brushed the ornate bunch of satin at her hip, slick and stiff and cold to the touch after the warm wool jersey. I suppose every man has known a stray impulse to give a good yank to one of those elaborate rustling structures of satin or taffeta with which women like to call attention to their hips and rear ends. Tonight I gave the impulse free rein, and the stuff came unstitched, protesting shrilly. There seemed to be yards of it, and startlingly great portions of her dress came with it; I heard her gasp as she felt it disintegrate about her. She stopped fighting me and lay passive as I got a fresh grip on what remained, preparing to strip her completely..

Then, lying there together like that, sprawled across the big iron bed, breathing heavily, we were both still, listening to a racketing sound outside: somebody in the railroad station had started up one of the small motorized bikes of which the Swedes are so fond. They’re kind of weak in the muffler department, and you can hear them a long way off. This fellow seemed to be right under the window. He was having trouble, apparently. The thing coughed, spat, choked, and died. He kicked it again, and it caught, and he revved it up until the noise was a high shrieking whine, and I couldn’t see how he could keep from losing a valve or two, except that those damn little two-cycle motors don’t have any valves. Then he rode away, sputtering, leaving silence behind him.

I raised myself slightly and looked down at Lou. She had relaxed; her face showed a kind of peace under her disordered hair.

“All right, Matt,” she whispered. “All right. Go ahead. You’ve got that much coming.”

She’d promised something—implied if not spoken— and she was going to pay off, even if she’d just heard the all-clear signal and knew there was no further need to keep me occupied. Suddenly I was neither drunk nor angry. I just felt kind of foolish and ineffectual, stopped in the middle of ripping the clothes off a woman I couldn’t bring myself to hurt and didn’t, I realized, particularly want to rape. I mean, sex shouldn’t be a weapon, an instrument of hate. It’s something you share with a woman you like. At least you can try to keep it that way.

I got up slowly, and looked at her lying there across the bed, tangled in some inadequate wreckage that no longer bore much resemblance to clothing. I found myself, for some reason, remembering how Sara Lundgren had looked after Caselius and his boys got through with her. Well, at least Lou was still alive; and I’d n

ever claimed that Caselius and I weren’t pretty much on the same level, morally speaking. It remained only to see which of us was tougher, which was smarter.

I started to say something bright and clever, and stopped. Then I started to say something apologetic, which was even sillier. It wasn’t a time or place for speeches, anyway. I just turned and walked out of the room.

22

In the hall outside my room, I had the key in the lock. I was ready to push the door open and step inside, when it occurred to me that was the way people went and got themselves killed. They got themselves all upset about a woman or something, and forgot to take stock of a changed situation that might hold danger.

If everything had gone according to plan, my situation had changed drastically—at least Caselius would be thinking it had, which was what counted—and I remembered very clearly what had happened to Sara Lundgren when our boy decided he had no further use for her.

I reached in my pocket, got the Solingen knife, and flicked it open. Standing aside, I gave the door a push and waited for it to swing all the way back. Then I waited a little more. If there was anyone inside, he could watch that lighted doorway for a while and wonder whether the first object through would be a human being or a hand grenade. It would do his nerves good, from my point of view.

When I went in, I went in fast and low, at a slant. It would have taken a very good man to pick me off in the brief moment I was silhouetted against the light. I hit the floor inside and kept rolling, and nothing happened. You feel kind of silly, getting yourself bruised and dusty for nothing, but it’s better than being dead. I lay there in the dark long enough to decide that if I wasn’t alone in the room, the other guy must have passed out from holding his breath. Then I got up and moved cautiously to the window to pull the blind, keeping well to one side, before I turned on the light. I didn’t look out. A white face makes a swell target, and I wasn’t curious. If there was a sniper outside, that was a good place for him to be. He didn’t bother me a bit, out there.

The Two-Shoot Gun

The Two-Shoot Gun Mad River

Mad River Texas Fever

Texas Fever Ambush at Blanco Canyon

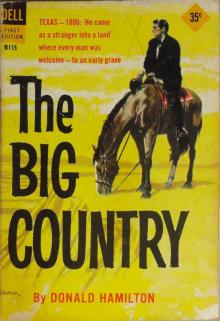

Ambush at Blanco Canyon The Big Country

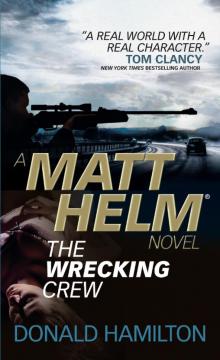

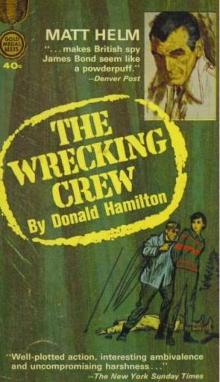

The Big Country The Wrecking Crew

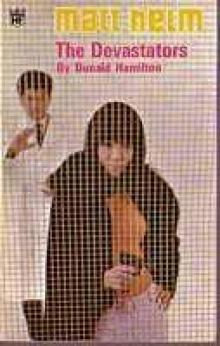

The Wrecking Crew The Devastators mh-9

The Devastators mh-9 The Wrecking Crew mh-2

The Wrecking Crew mh-2 The Shadowers mh-7

The Shadowers mh-7 The Ambushers mh-6

The Ambushers mh-6 The Betrayers

The Betrayers The Terrorizers

The Terrorizers The Poisoners

The Poisoners The Devastators

The Devastators The Silencers mh-5

The Silencers mh-5 The Interlopers mh-12

The Interlopers mh-12 The Shadowers

The Shadowers The Annihilators

The Annihilators The Vanishers

The Vanishers Night Walker

Night Walker The Revengers

The Revengers The Frighteners

The Frighteners The Infiltrators

The Infiltrators The Intriguers mh-14

The Intriguers mh-14 The Steel Mirror

The Steel Mirror The Menacers

The Menacers Assassins Have Starry Eyes

Assassins Have Starry Eyes Death of a Citizen

Death of a Citizen Matt Helm--The Interlopers

Matt Helm--The Interlopers The Removers mh-3

The Removers mh-3 The Demolishers

The Demolishers Murder Twice Told

Murder Twice Told The Poisoners mh-13

The Poisoners mh-13 The Ambushers

The Ambushers Death of a Citizen mh-1

Death of a Citizen mh-1 The Silencers

The Silencers The Removers

The Removers The Intimidators

The Intimidators The Damagers

The Damagers The Menacers mh-11

The Menacers mh-11 The Retaliators

The Retaliators Murderers' Row

Murderers' Row The Ravagers

The Ravagers The Ravagers mh-8

The Ravagers mh-8 The Threateners

The Threateners The Betrayers mh-10

The Betrayers mh-10